The next Tour destination that was relevant to my family story, was the small town of St. Johnsbury, Vermont, in Caledonia County, one of three counties near the borders with New Hampshire and Canada, which, mostly for marketing purposes, are together referred to as the Northeast Kingdom. I had only uncovered my connection to that town relatively recently, but I was distinctly looking forward to my visit. Before I expand on my personal link, however, I want to mention some aspects of the route I used to get there, and about the town as it is today.

I covered the distance from Newstead, NY to St Johnsbury in eight and a half days, which should have required a just slightly relaxed pace, but turned out to be a tougher segment thanks to one day that was totally rained out. In fact, most of the remaining days involved less than perfect weather, with either cold, or occasional rain, or cold and rain. Nevertheless, I managed to stay on schedule by pushing forward a little harder, which included the first two imperial centuries of the current Tour.

Another factor that made the segment seem a little more tedious than I was expecting was the occasional presence of poor cycling conditions. Most of the road surfaces on the route were actually quite good, with better shoulders than I remembered being present when I lived in the region a few decades ago. The examples that weren’t so good would have been tolerable in the absence of heavy traffic, which wasn’t always the case. In the west, it is usually easy to predict, just by looking at a map, whether a certain road will be busy or quiet. However, in the east this does not always work, and a minor road can turn out to be uncomfortably crowded. An example that exhibited both heavy traffic and a poor surface was Vermont Highway 15, a secondary road that I thought would be pleasant and easy. In reality, the shoulder it claimed to possess was little more than a 60km-long linear pothole, and the number of motor vehicles was at least four times more than one might expect for a road in rural Vermont.

In this case, I was fortunate to be able to avoid that particular highway by making use of the Lamoille Valley Rail Trail. Normally, I avoid recreational cycling trails on tour, since they often exhibit one, or more, deficiencies, including meandering around and adding unnecessary distance to the day’s route, terminating unexpectedly in the middle of nowhere, or consisting of a soft and soggy surface. The latter seemed quite likely in this case, given all the wet weather that had been in the region in recent weeks. Fortunately, I took that trail on one of the few pleasant days I had recently seen, and though it added a small amount of distance, it worked out well, and saved me some anxious hours on a bad highway.

I had investigated the local area enough before starting the Tour that I knew I was going to enjoy my stay tremendously. The town of St. Johnsbury, with a population of almost 5,000 residents, is off the charts in terms of what a small town should be, in terms of livability and culture. Like numerous towns in New England, there are many fine homes and buildings, built with care in the classic style. However, unlike some other places there is relatively little modern ugliness surrounding the historic part of the town. My direct ancestors lived in the town from 1790 until around 1839, and it is unfortunate that they didn’t stay longer, because the town really blossomed in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This occurred primarily thanks to the efforts of one prominent family, the Fairbanks. A member of that particular family was the inventor of the platform scale, which soon became an essential implement of the late Industrial Revolution. This allowed the Fairbanks to amass a substantial fortune, a relatively sizable fraction of which was used to fund a number of impressive enhancements to the town. One was the establishment of a High School, which still operates today. While it is as costly as you might expect these days, it is also part of the school charter that children of the town can attend as if it were the local public school.

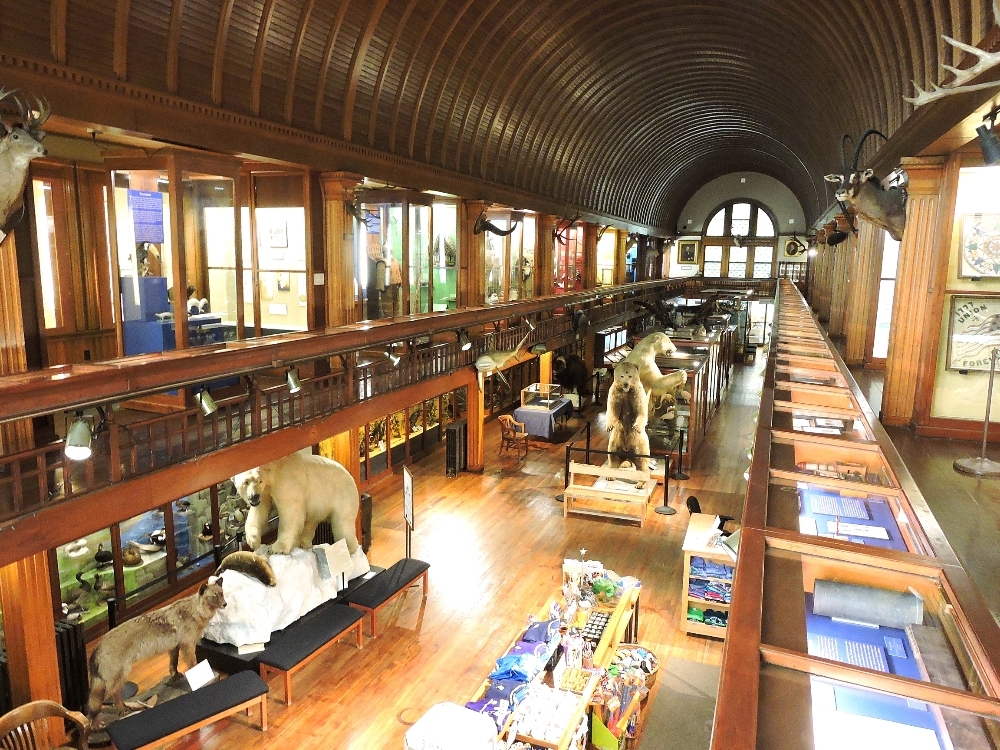

An excellent Natural History Museum and Planetarium in the town center also bears the Fairbanks name. Like many wealthy people in the Victorian age, members of the Fairbanks family were avid collectors of artifacts and interesting items from around the World. These were displayed in their home in a Cabinet of Curiosities,

as was the fashion of the time. When their collection grew too large for that, it was gifted to the town to start the museum. There are some fine objects on display ranging from tools to clothing, to musical instruments. However, about half of the exhibit is taxidermied birds and mammals. While I would have been very impressed by that when I was a child, now, having seen many of those species alive in the wild, such displays are less appealing to me.

One of those that did resonate with me, however, were the two featherworn examples of the Carolina Parakeet. That species, now extinct, was the only parrot of eastern North America, and its loss is one of the great tragedies of this continent. I have a reproduction of Audubon’s print of that species hanging in my living room, as a reminder of what we once had. This poor pair will be my only real experience seeing the former parrot of my homeland, and it is hard to imagine what it would have been like if the great flocks that once flew over the place where I grew up still existed.

A third gift to the town by the Fairbanks was its Library, The St. Johnsbury Athenaeum. Its building, built in the French Second Empire Style, and it collection of books, are nice, though not particularly unique on their own. Where this facility stands out is that it also houses an impressive gallery of fine art. European paintings are not always my favorite, but there are also some nice examples from the Hudson River School, which I appreciated. The standout piece, however, is Albert Bierstadt’s three-meter-tall The Domes of Yosemite. The first short tour I rode after moving to the West was to Yosemite and I remember later standing on the specific vantage point captured in the painting. Seeing it now, during this Tour, was a nice connection to my earlier travels.

The reason I am mentioning the nice qualities of St Johnsbury now, is that many, or even most, towns that existed in America during that time period were similarly attractive. Of course, not every one of those could have a fine gallery in their library, or a respected private school, but all could have resisted the calls to bulldoze, or simply abandon to atrophy, what was nice about their towns in order to replace it with dehumanizing sprawl in the name of modernity or progress. When I lived in New England in the 1990s, Vermont was standing firm in an effort to resist the encroachment of certain big-box-style chain stores. This was not entirely successful, but it affected the process enough that some towns were able to retain much of their traditional character. St Johnsbury today has relatively minimal amounts of sprawl compared to other towns its size, and the benefits of that policy are easy to see.

For a half century, or more, my family only knew our Ayers ancestors back as far as the children who lived in Newstead, my great-great-grandfather, and his siblings. This was because we have an old family Bible containing hand-written notes of their birth dates, a common practice for families from that time period. However, their parents were only listed as Father and Mother, which ended the trail there. Eventually, as more digital records became available online, I learned that their names were John Ayers and Hannah, maiden name unknown, and that they previously lived in Vermont. In terms of usefulness for research, John Ayers

might as well have been John Smith,

given the frequency of the former name in early New England.

It is said that all the Ayers with New England roots trace their lineage back to the original immigrant who arrived in the 1630s, and who I may come back to in a later post. However, for a long time I had no way to locate my potential link to that man. Eventually, the advent of genetic genealogy revealed that I was indeed a descendant of the first Ayer to arrive in America, and a friendly exchange of messages with another researcher led me to a potential family living in St Johnsbury. That family had a son named John and a older daughter named Sarah, who was married to man from the Ball family, and who had relocated to Newstead, New York. I finally found my 3rd-great-grandfather.

Samuel Ayer, my 5th-great-grandfather, was the first of my family to arrive in St Johnsbury, and he was one of its earliest residents, starting his homestead in the early 1790s. He had briefly participated in the Revolution, though his service did not appear to have been very noteworthy. His home was just to the north of the town center on what is today called Crepeault Hill Road. Close to his home site is a small cemetery, now named the Ayer-Hawkins Cemetery, where Samuel, my 4th-great-grandfather Hezekiah Ayers, and their respective wives, Mary Carlton Ayer, and Jemima Quimby Ayer, had been interred many years ago. Hezekiah's monument is the one that needs to be straightened. I wondered, as I visited, whether DNA from that long ago still persisted in their remains, since, if so, the coding of their Y-chromosomes is identical to mine, and that made me pause and think for a while.

This appears to have been a wonderful location for a homestead, and Samuel and his family must have certainly appreciated views like this one, on many a fine spring morning.

When I visited, I was pleased to see that the location where the original house stood is still being used for some form of agriculture today, and escaped the fate of less-than-ideal development that befell my family’s farm in Newstead. The current house on the site, at the left of the photo below, looks like it could possibly be over 200 years old, but it’s hard to say, and the friendly gentleman who has lived there for the last fifty years couldn’t say for sure either. Nevertheless, I would like to think that it was the house that Samuel Ayer built.

Hezekiah Ayer would frequently travel from this place to the adjacent town of Lyndon, Vermont to obtain milling services. It is likely that, on some occasions, his son John Ayers accompanied him, and on one of those visits may have met Hannah Miles, the daughter of William Miles, a miller from that town. Hannah and John were married some time around 1816 and raised a total of nine children, eight of whom were born in Vermont, with the final coming forth in Newstead. For an unknown reason, perhaps because childbirth often occurred at home in those days, none of these children appear in the Vermont Vital Records database, and a visit to the well organized Town Clerk’s office in St Johnsbury also did not reveal any mention of them.

However, I know some of their stories now, and since no one should ever be forgotten, I will briefly mention them here. Mary was the oldest daughter, she married Solomon Stever and lived a long life in Newstead. Abial, my great-great-grandfather, as I have previously mentioned, married Hannah Ferguson and also lived a fairly long life in Newstead. George married a girl named Lucy, whose family remains a mystery, but he died at the relatively young age of thirty-six. Julia Ann led a seemingly dissatisfying life but eventually married Alfred Perry, a Civil War Veteran who had been a boarder and laborer with the family for a time. Luman also died young, at the age of thirty, without a family of his own. Martha married John Parker, and they had three children together, but she died at the age of thirty-three. Peter was the only sibling to leave western New York, migrating to Wisconsin when he was thirty years old. There he married twice, raising five children with Edith Parrish, though his final fate remains a mystery. Some of his descendants continued west, and some eventually lived not far from where I did in Oregon. The youngest sibling, and the only one born in New York, Lorenzo Ayers, did not live longer than age twenty-one.

I feel that of all my departed ancestors and relatives, the one I would most like to speak with, if that were somehow possible, would be Julia Ann Ayers, my 3rd-great-aunt. She seems to have been empathetic, but also strong willed. She had a son named James with a man named James Smith, though his status was somewhat ambiguous. Young James used the surname Ayers, however, and seems to have led a disadvantaged life, working for a time as a stationary engineer, but living the last years of his life in the Genesee County Home. When James was still young, Julia Ann also took on the task of caring for two of her brothers who sequentially developed terminal cases of tuberculosis. Not long after that, the head of the family, John Ayers, passed away, and her mother Hannah’s health began to decline. Julia Ann was living on her own by then, but Abial, my great-great-grandfather, pressured her into returning home to care for their mother, who seemed to be exhibiting the effects of a stroke or general dementia. After all of that it is not surprising that, a few years later, when she married Alfred the couple would move to nearby LeRoy, New York, and live out a quiet, inconspicuous life together. I think that I would enjoy conversing with her over an afternoon repast, and listening to what she had to say about life.

The above accounts for eight offspring of John and Hannah Ayers, but there was a ninth, one even more mysterious than the rest of the family had been, as only a birth date is legible in the family Bible. It is too long a story to relate here, but that child was oldest son of the family, a boy with the uncommon name of Admiral Ayers. For some reason, his life did not turn out as anyone would have wished. He spent 18 of his first 44 years in prison, three in Vermont, and 15 in Ohio. The reason his name is difficult to read in the Bible—someone tried to erase his record!

I am immensely satisfied to have finally uncovered the story of this family after many years of trying. I am also glad that I have now been able to see where they lived their lives, even more so because the places they lived are also places that I know I would definitely have enjoyed living in as well.