Within the genealogical community, it has long been stated that anyone who has the surname Ayers, or one of its variants, and who also has a family connection to New England, is almost certainly a descendant of the founding colonists of that family, namely John Ayer and his wife Hannah, of Haverhill, Massachusetts. For most of my life, including the years I spent as a graduate student in the western part of that state, this circumstance was unknown to me. Had I realized at the time that my paternal line ancestors had lived nearby around 325 years earlier, I certainly would have taken the time to explore some of the places that would have been familiar to them. Now, many years later, when Boston was the most convenient waypoint for my flight back from Iceland, I knew that I needed to spend a few days in that area, even if there was little tangible evidence visible related to their presence.

John Ayer, my 9th-great-grandfather, came to Massachusetts with his family from Wiltshire, England in the late 1630s. As it turned out, I knew that I was his descendant for some time before I knew exactly how I was connected to him. That was because my Y-chromosome haplogroup, revealed by one of the first genetic tests I undertook, placed me firmly within the group of Ayers men who were all descendants of John. In fact, it was me who eventually determined that all men who are descendants of John possess the terminal SNP on their Y-chromosome of R1b-Z278. That fact revealed some interesting information about the ancient history of my family, but I will save a discussion of that for a possible future post. For the time being, the World2 Tour had brought me back to my Colonial New England roots, so this post will focus on that area.

John and Hannah—most of her family history remains unclear, unfortunately—already had a large family when they arrived, but still took some to locate their eventual permanent residence. They appeared in the records of both Ipswich and Salisbury, Massachusetts, before finally settling in Haverhill, then known as Pentucket, around 1640. Few details about their personal lives prior to their arrival have persisted through time, probably in part due to the fact that they were a Puritan family, and some facets of their emigration, such as the sea passage they arranged, may have been kept secret to avoid persecution. However, once they had established themselves in Haverhill, John and Hannah settled into a relatively stable life, raising their nine children, and working a basic, but productive farm typical of those of the early colonists. Their extended family flourished, and it has also been said that by 1700, thirty percent of the residents of Haverhill were their descendants.

I knew that there would be some footprint of this family to be seen in the town today, but I expected that it would be fairly minimal in its visible appearance. Therefore, I chose to avoid cycling through the congestion around Boston and made my way to Haverhill using the local commuter rail service. In the Industrial Era, Haverhill had become a prosperous mill city, notable as a center for the production of shoes. Like most similar towns, the Post-industrial Era brought with it a decline in the area’s fortunes, so I was unsure how appealing the city would seem during my visit. As it turned out cycling around the town was relatively pleasant, and, in general, I rather liked the city, which has managed to somewhat effectively repurpose many of its classic brick-faced buildings.

The first place I saw that was connected to me in some way was a nondescript little hillside street named Ayer Street, presumably after John, or some member of his close family. Today, it is not one of Haverhill’s most elegant addresses, but I took the opportunity to zig-zag down its path by bike a few times, nevertheless.

A few kilometers outside of town is a smaller locality known as Ayers Village, which in the past was also the site of a few small shoe factories. Today there is only a small cluster of homes and some unrelated small businesses remaining, and I was a little disappointed that there was no signage anywhere around that would indicate the name of the place. Continuing westward, the road becomes Ayers Village Road, but it is also unmarked, which continued to annoy me. Only one, rather lame, sign finally came into view near the end of the road, which was the only indication I could find demonstrating my connection to that place.

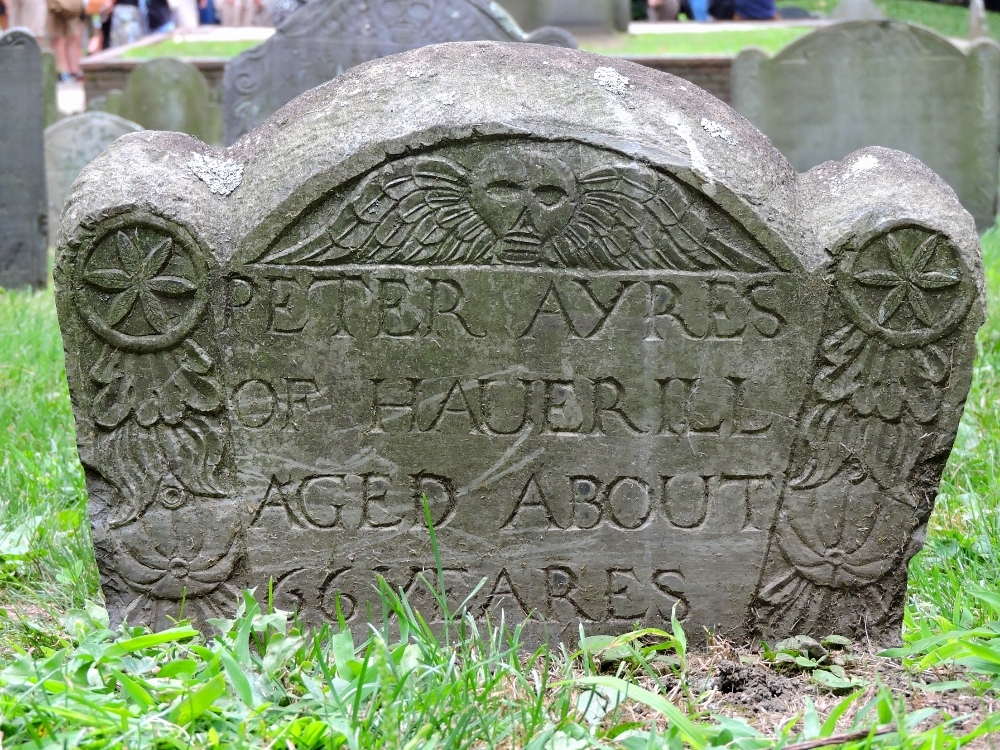

My 8th-great-grandfather was the middle child of John and Hannah’s group of nine, Peter Ayer. He would have been a young child, around five to ten years old, when the family made the perilous voyage across the Atlantic, which must have been quite an adventure, especially compared to a crossing on a container ship, like I may make use of on my Tour. Considerably more details are known about his adult life, compared to his parents, and they do seem to indicate that during his later years he became a respected member of the local community. It is believed that he was also a Puritan, and he was certainly an officer in the military of the time. This may reveal that he, perhaps unappealingly, as seen with a modern point of view, could have participated in the violent conflicts between the colonists and the local tribes as the English sphere expanded. Within his own community, however, his accomplishments were somewhat more appealing. He was a Freeman, a yeoman, juror, constable, and later in life served as Haverhill’s representative to the Colonial equivalent of a State Legislature in Boston. He was likely working in that capacity when he died in 1699, and this service may have earned him a place of internment in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground, where other early colonists, and several notable figures were laid to rest, including John Hancock, Crispus Attucks, Samuel Adams, Peter Faneuil, and Paul Revere, whose monument is only three meters away from Peter’s.

Peter married Hannah Allen, from another prominent Colonial family, who survived him by many years. She remained in Haverhill, and her monument can still be seen at the Pentucket Cemetery.

In one historical account, it is stated that Peter Ayer built his house at 621 Washington Street in Haverhill, though, presumably, that street had some other name in the 17th century. Unfortunately, while the house existed as late as the 1960s, it is gone now. However, the Special Collections of the Haverhill Public Library has a photograph of it, probably taken some time in the late nineteenth century. Inscriptions on the back state that the house belonged to Peter’s grandson, so I can not be completely sure that the photo is of the same house that Peter built, though it may in fact be identical. Either way, it belonged to one of my ancestors, and seems to have been of a quality that would have been possessed by hard-working colonists of that time period.

One of Peter and Hannah’s sons, my 7th-great-grandfather, Samuel Ayer, also built a house in Haverhill, and it was pleasing to see that his still exists. It remains a private residence, though it has been out of my family’s hands for many decades, so seeing its interior is not possible. However, a view from the street was adequate for me, and I was happy to finally see something substantial from my family’s past in the town. Built in 1712, the house is located in an appealing neighborhood in a historic part of Haverhill, adjacent to a small square containing attractive greenery and monuments.

My direct line of ancestors continued to live in Haverhill for one more generation, until another Samuel Ayer made his move to Vermont, which I have already mentioned. However, since I was in the area I decided to have a look at some sites relevant to some of the collateral branches of my family. That would also give me the opportunity to get back on the bike, albeit for a fairly brief time, which I really needed after all the time off caused by my visit to Greenland. The first stop I made was in Lowell, Massachusetts, reached by an easy ride from Haverhill.

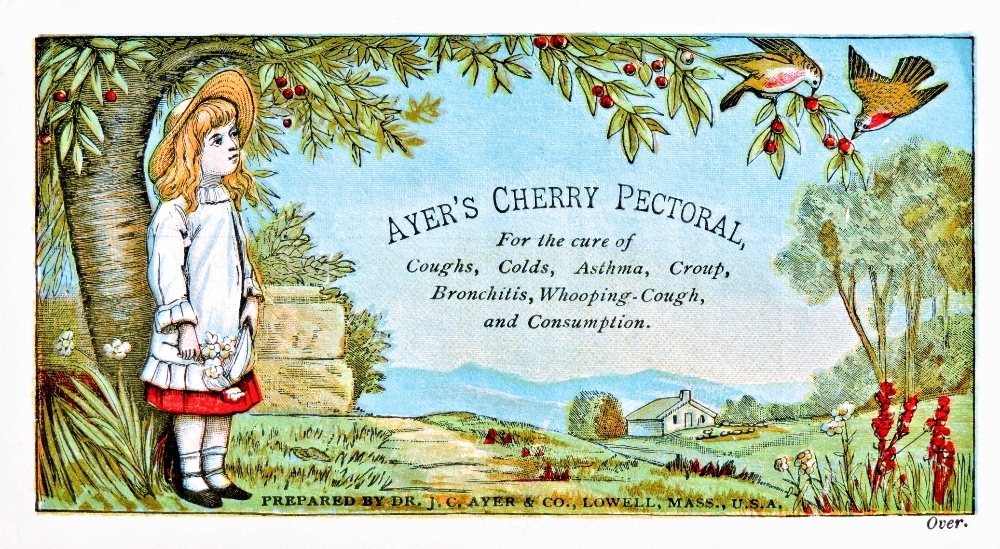

James Cook Ayer was my sixth cousin, four times removed, conected to me through Peter Ayer, and he and his brother were among the few members of the extended family of New England Ayers to achieve any sort of fame to an appreciable extent. He did this by becoming one of the leading Patent Medicine magnates of the mid-nineteenth century. In that era, Patent Medicines, were usually solutions, or perhaps a better term would be concoctions,

of extracts, other natural products, or occasionally inorganic substances, designed to be drunk or applied to then skin, in hopes of curing various ailments or conditions. J. C. Ayer started his company in Lowell, and quickly achieved considerable success and wealth. The line of products on offer included cures for respiratory problems, malaria, hair loss, and general loss of vigor. As someone whose previous profession was Chemistry, I would be somewhat more proud if those cures were a little more like actual medicine and less like Snake Oil. However, it is said that Ayer employed some very basic aspects of the Scientific Method in his product development, and Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral contained a small amount of morphine, so at least it must have had some kind of effect, for better, or worse. Ayer’s Sarsapirilla apparently tasted good, at least. The latter product became very popular, and when my great-great-grandfather, Abial Ayers, passed on, a case of that particular treat was in the inventory of his estate.

The J. C. Ayer Company occupied multiple buildings in Lowell at its peak. At least one of those is still standing today, though now it is known as Ayer Lofts, and is a live/work facility for artists. Another remnant from that time is J. C. Ayer’s stone house on Pawtucket Street, which now belongs to a convent.

One important way J.C. Ayer built his company was as a pioneer of creative print and textual descriptions of his products. These included almanac-type publications, laced with thinly-veiled product advertisements, and artistic print cards, early versions of American Pop Art advertising. While I am someone who finds most marketing generally distasteful, and something we would be better off without, at least his cards were, usually, esthetically appealing.

At some point, James’ brother Frederick joined the business, but in a more managerial capacity. He also became wealthy as a result, and primarily used his fortune to move up the social ladder. He built what became known as the Ayer Mansion in Boston’s fashionable Back Bay neighborhood. That particular dwelling, while not especially extravagant by gilded-age mansion standards, is notable for being one of the few private homes designed by Louis Tiffany. Tours are available, once a month, but that didn’t fit in with my Tour schedule, so I had to settle for a view of the exterior.

My last stop in this section of the route was a town that shares the root of my family name, specifically, Ayer, Massachusetts. I reached that small town by continuing west from Lowell on the same day. The origin of its name is not quite as historic as I might have liked, however, and. as a town established in the 1870s, quite new by the standards of New England, it is also slightly more modern in appearance. That essentially means that today it seems a little frumpy, having fewer classic homes and buildings that would have been worth the effort to maintain over the years. It is nice enough, overall, relative to similar towns elsewhere, but there was little for me to see there, so I primarily relaxed after the first significant day of cycling I had put forth in what had seemed like a long time. The one noteworthy place of interest provided the reason the town had been named Ayer in the first place. For it was James Cook Ayer who donated the funds to the fledgling town it needed to build its Town Hall.

Lest anyone think that I have any sort of personal connection to that sort of nineteenth-century new money

today, it is worth noting that near the end of his life, James Cook Ayer made an unsuccessful attempt to be elected to the U. S. Congress. That failure caused him tremendous stress, leading to a nervous breakdown, and he spent his remaining years in an Asylum, squandering most of his fortune. Or, perhaps he had consumed too many of his own products, and they actually weren’t as relaxing as he claimed they were.

I very much enjoyed visiting all of the family history sites I have seen so far during World2, even though most of my stops were rather brief. Doing so added a nice dimension to the Tour, of a type that I have never been able to incorporate into any of my earlier tours, though it certainly would have been nice to have known about some of those places in years gone by. There may be a few more posts I will be able to make to add to the Origins series, but a considerable distance must be covered before that can occur. I hope I will make it that far.