Like many people who research their family history, I have spent a considerable amount of time working on the branch of my family that belongs to my paternal line, those ancestors who made up the chain of grandfathers on my father’s side of the family, and who all would have had some version of the name Ayers. One reason for that was that, as I have already mentioned, there had been a frustrating gap, now thankfully solved, at my third great-grandfather on that line, a break that I always felt should not have existed. Of course, it is also common for people to place an inordinate amount of importance on the branch of their family that gave them their surname, even though the practice of inheriting that name from one’s father is particularly arbitrary. That is a rather unfortunate, and even a limiting, viewpoint. During the time periods I will present in this post, beginning twelve generations back and drifting vaguely further back for perhaps two hundred more, at any given point in time the number of my grandparents living then would have numbered from a little as four thousand to an unknowable amount in the millions. Each of them has given me an equal contribution to my personal story and should be of equal value to me, even though my name came from only one man.

However, today there is another compelling reason why many people choose to put forth extra effort to investigate that part of their families. Specifically, the fact that, in addition to their surnames, men inherit their Y-chromosomes in an unaltered form from their fathers provides an effective method to learn about both recent and ancient ancestry on that branch of one’s tree. I believe that I was the first man among the many thousands from my genetic Ayers lineage to test his genome to a sufficient depth to identify the most recent mutation of the Y-chromosome, at least from the set of those mutations that had already been identified by 2015. In so doing, I confirmed that I was indeed a descendant of John Ayer, of Haverhill, the early-seventeenth-century immigrant who was the progenitor of virtually all of the Ayer(s) of New England. It was also my good fortune that, once that fact was known, I was able to instantly extend my genealogy back several more generations, thanks to the previous efforts of many traditional genealogists who, in the twentieth century, had determined that John Ayer’s family origins were in Wiltshire, a lovely county in southwestern England. Today, that county is most famous as the location of Stonehenge, though that ancient temple preceded my family’s presence there by at least two millennia.

My family’s ancient history, as revealed by my Y-haplogroup, was both interesting and surprising to me. In general terms, we are members of the group labeled R1b, which is nothing special, since that group is by far the largest known for people with western European heritage. R1b people were thought to have entered Europe from western Asia at the end of the Neolithic period, spreading westward, and bringing with them Bronze-Age technologies and possibly domesticated horses. Their general path is thought to have been through central Europe, north of the Alps, towards the Atlantic, and, during the latter stages of that movement, they are sometimes referred to as proto-Celts.

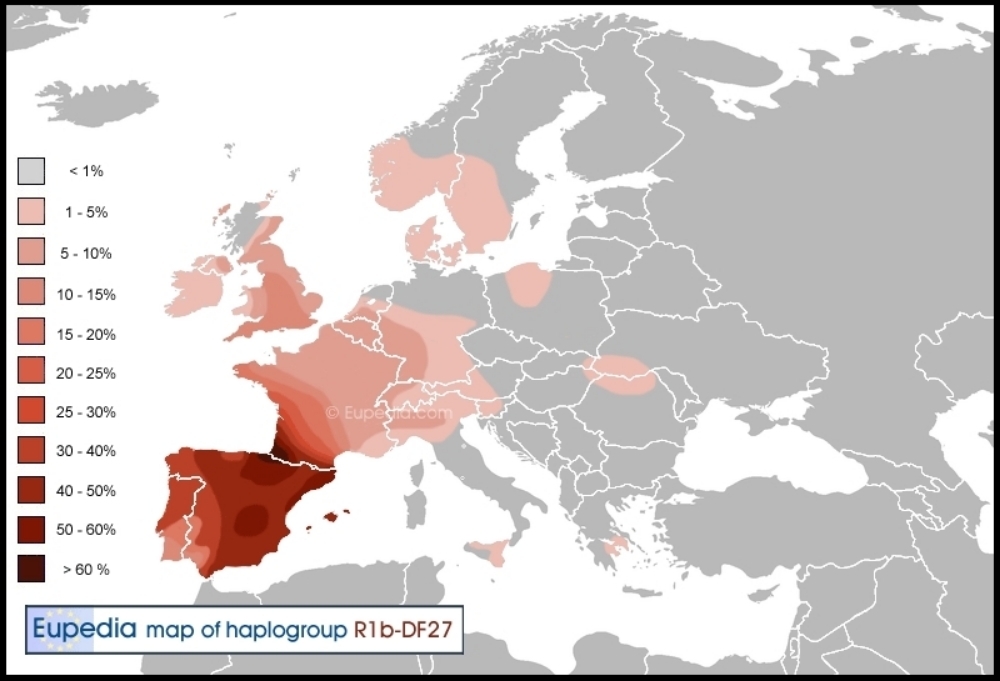

However, it was when my more recent mutations were identified that things began to get interesting. My final haplogroup, as of 2015, is R1b-Z278. The estimated age of the Z278 mutation is approximately 4,500 years before the present, meaning that the first of my grandfathers to carry it was born sometime around 2,500 BCE. By analyzing the geographic location of members of that group alive today it is possible to make a reasonable prediction about where that man lived. This has been done by others, and the results can be seen in the heat map shown below. A clear predominance can be seen in the western Pyrenees, in what is today the Basque region of Spain and the Gascony region of France, which is therefore the most probable birthplace of my distant ancestor. Four thousand five hundred years ago, people living there probably lived in small, semi-permanent settlements built using traditional methods and materials, and possessed an early Bronze-Age level of technology. The only city-building civilizations contemporary with them existed in Fifth-dynasty Egypt, not long after the completion of the Great Pyramid at Giza, Mesopotamia at the start of the Assyrian period, Crete for the Minoans, the Indus Valley, and Norte Chico on the coast of Peru.

In a circumstance that is both intriguing and annoying, it seems that this history may have already been partially understood. Many years ago a one-name-study Web site was created for the all the variants of my surname, primarily drawing on traditional genealogical methods. One article contained a line of text that was particularly interesting for me: There are some who say the family’s origins were in the Pyrenees…

Many attempts to find out who said that all proved to be fruitless, which saddened me tremendously. I would love to know why they thought that to be the case, and to let them know that they were almost certainly correct! Perhaps, with patience, I will one day make that connection.

The first known appearance of my family in Wiltshire occurs in the mid-twelfth century. Therefore, there is a gap of over three thousand years over which my family history is unknown, and for which it will likely remain so. However, it can logically be assumed that a slow migration occurred, probably along the west coast of France. This may have been associated with the Maritime Bell-Beaker people, a coastal subculture of the wider Bell-Beaker culture of Europe, so named for their distinctive pottery. Whether this occurred stepwise over a hundred generations, or involved a few longer movements can never be known. However, as will be expanded upon shortly, at the end of that period my ancestor probably lived on the northern coast of France, perhaps in what is now Normandy or Brittany.

Consequently, the arrival of my family in Wiltshire appears to have been associated with the Norman invasion and conquest of England. However, the approximate birth year of our earliest known ancestor was around 1140, about seventy-five years after the conquest, but still well within the era of Norman Britain. Therefore, it is not possible to say whether we had an ancestor who was a soldier in Duke William’s invasion force, or if he was instead a merchant, artisan, or tradesman who crossed the English Channel in the following decades. In either case, he probably made that crossing in a boat similar to the ones shown below, which appear in the famous Bayeaux Tapestry, a seventy-meter-long embroidery that tells the story of the conquest, and which I enjoyed viewing once I had arrived in France. If we did have an ancestor depicted in the tapestry, he was most certainly not a nobleman, aristocrat, or a member of the clergy, but rather one of the more ordinary citizens. In England, our ancestors appear to have remained outside of those privileged groups as well, but some seem to have held positions of respect in civil society, and, in fact, that circumstance is definitely more appealing to me.

The mid-twelfth century is around the time when the use of family surnames became the fashion in Britain, and surrounding areas, so prior to that our ancestors would have been given simpler names that would have been of little use in identifying them today. There is a fanciful legend floating around that claims to explain the origin of all the variations of the name Ayers, but, frankly, it is ridiculous and certainly apocryphal, so I will not mention it here. As usual, the more likely explanation is just as interesting. The man born in 1140 had the name Humphredi Le Heyr. Researchers more skilled than me have spent many hours reading through historical documents written in Latin or French to elucidate the origin and meaning of this name. The article Le

included in the name was common in Norman Britain, as French was commonly used in important matters. It is believed, then, that Heyr represents what it appears to be, specifically, heir,

and so the name was the heir of Humphrey.

What is not known for sure is what this man inherited, and from whom. One theory states the the Le Heyr family was closely connected to the Blount family, also of Wiltshire, (Blount is Old French for Blonde

) and that Blount was the original family name. However, I have examined the haplogroups of the Blounts that been reported so far, and, though the number of people tested is fairly small, I don’t think that there is a real connection.

Of more interest to me is the possibility that at least some of the Le Heyr men held the position of Hereditary Foresters. In Medieval times, forests were one of the primary resource bases that supported the activities of societies. As forested land had already begun to dwindle by then, such a position would have been very important, and garnered a considerable amount of respect for its holder. As someone who has always appreciated forests, and has plans to begin a project related to that field, nothing would make me happier than if the idea that my Le Heyr ancestors had once inherited that position turned out to be true.

Humphredi Le Heyr was said to have lived in Bromham, a village in western Wiltshire, and an additional five generations of his descendants spent their lives there as well. I took the opportunity to ride through there at the start of my visit to Wiltshire. Today, Bromham is an attractive small village with, perhaps, a few hundred residents. Like many towns in Britain, the oldest structure in town is the Church, in this case Saint Nicholas Church, which has existed since the late eleventh century, and so would have been familiar to the Le Heyr families. The north and west walls of the structure, which is currently used as a school, date back to that time, and can partially be seen in the second image below.

By the late fourteenth century, the family had moved about ten kilometers to the southeast, to another small village called Urchfont. At this point the spelling of the surname had evolved to Eyre, the variant that is the most commonly used in the British Isles to this day. Four more generations of my Eyre ancestors resided in Urchfont, which is smaller than Bromham, but perhaps even more attractive thanks to its many beautiful structures with traditional thatched roofs. The Eyres would have spent much of their time in Saint Michael and All Angels Church, in which the Chancel dates back to the year 1230, prior to their arrival in the village. Most of the gravestones in the Churchyard are now weathered and illegible, so I was not able to look for any Eyres there. However, the more modern World War I/II monument lists a John A. Eyre, who was killed in 1941, so I may have had relatives living in Urchfont at least until then.

The earliest of my Eyre ancestors for which there is a visible, physical record actually turns out to have been a woman, which is an extraordinary and pleasing circumstance. Specifically, this was Johana Cokrell, the wife of William Eyre of Urchfont, my thirteenth great-grandmother, and mother of John Eyre, my twelfth great-grandfather. My encounter with her is listed here out of chronological order of my visits, because her remains lie about eighty kilometers to the south, in Christchurch Priory, near the English Channel and the city of Bournemouth. William and Johana’s oldest son William, a grand-uncle of mine, went there to become a monk and eventually rose to the position of Prior of the Monastery. For reasons known only to her, Johana followed him to Christchurch and was still there when she died in 1503. Her monument is on the floor of the Priory, next to her son’s, and the inscription in Latin around the edge reads: Here lies Johana Cokrell, the mother of William Eyre prior of this church, whose soul may god bless.

From Urchfont I made my way to Salisbury, the Capital of Wiltshire, and the place of residence for the Eyres from around the 1550s onward. Along the way, I visited Old Sarum, the original site of Salisbury. Old Sarum had originally been a pre-Roman hill fort, but was greatly expanded when William the Conqueror had a castle and cathedral built at the site. Not long thereafter, when the crown and the church came into conflict, it was decided to move the cathedral to another location nearby, and once that was underway the entire site went into a severe decline. My ancestors would certainly have known of that place, but by the time they arrived in Salisbury it was probably already partially in ruins. Today, however, it is an interesting place to spend an hour or two, in order to contemplate its history.

Construction of the new Cathedral began in the year 1220 and it eventually grew to become one of England’s best known religious landmarks. Its notable features include a Medieval clock, the tallest spire in the United Kingdom, and an original copy of the Magna Carta. Certainly, many of my ancestors would have been very familiar with its imposing appearance. However, while the Cathedral was undeniably impressive and an interesting place to visit, the more relevant site for me was somewhat smaller.

So that the laborers who built the Cathedral could, during the forty years that were required for its construction, have access to a Church, a much more modest structure was built for them nearby. This was Saint Thomas Church, which still exists, and is now right in the center of Salisbury. This Church was probably my most anticipated visit in England, and it turned out that my timing, for once, was fortuitous. The building had been closed for renovations and cleaning for several weeks and its planned reopening day was scheduled for the second of the three days I would spend in Salisbury. Had I not already been running a few days behind my original schedule at that point, I would have been very disappointed.

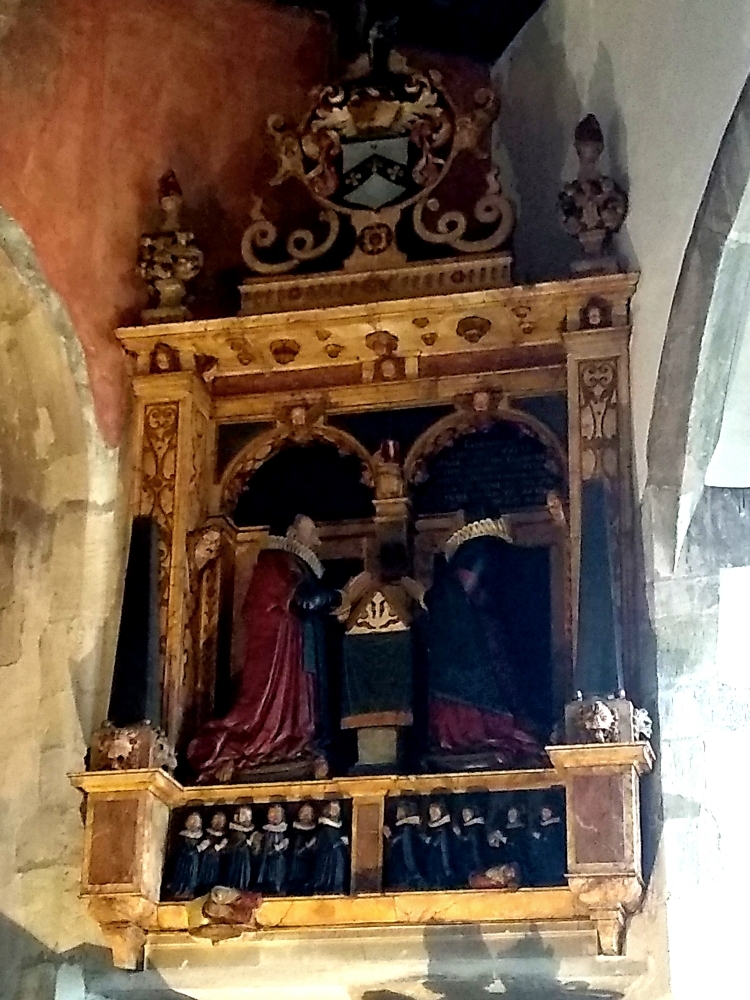

The most interesting feature for me was to be found in the Lady Chapel, which appears to be one of the older sections of the building.

In the upper right hand corner of the Chapel is a Monument to members of the Eyre family. At the top are sculptures of the Eyre heraldry designs, though these are not easy to see, since at some point in the Victorian period someone, as people were wont to do at the time, painted over the entire monument with opaque dark brown paint. (Egads!) In some of the images below, small patches are visible where this paint has recently been striped off, revealing the original full-color design beneath. The entire monument was planned to be restored starting just one month after my visit, so in that respect my timing was a little off.

Nevertheless, the important features to me are still visible. At the center are representations of Thomas Eyre and his spouse Elizabeth Rogers. They were my tenth-great-grandparents and the presumed parents of John Ayer, the immigrant.

It was difficult to get into a good position to see Elizabeth clearly, but her case was helped out by the text that is above her figure. It reads: Elizabeth Eyre was ye wife of ye worden Thomas Eyre, Esquire: mother of these XV children, a virtuous matron, a good neighbour, charitable, and an enemie to idolatry. In ye feare of God she departed this life ye 24th of December 1612, age 63.

Thomas has no such text above his figure, though there is chance that some existed before being painted over, and with luck that could be uncovered during the forthcoming restoration. However, being a male, there are other records that reveal somewhat more about his life. In addition to holding the position of warden of Saint Thomas Church, Thomas Eyre was for a time the Mayor of Salisbury and a member of Parliament representing Wiltshire, and so was clearly an important and respected man. I was also curious as to whether the carvings of Thomas and Elizabeth represented their actual likenesses, or not. However, in talking to members of the Church who were involved with the recent renovations, the consensus seemed to be that the figures were probably based on generic man

and woman

models. It is probably safe to say, however, that they both frequently wore ruff collars.

I had been aware of the important events of Thomas Eyre’s life before I left home, but one rather amusing anecdote was revealed to me in Salisbury. The image below shows a small door in the north wall of Saint Thomas Church. Today, it opens onto a narrow spiral staircase, made of stone, that leads up to the roof of the building. However, in the late sixteenth century it took one to a small upper floor apartment. For several years an Alchemist apparently lived in that spot, and his story had recently been investigated by a local resident. It seems that the man was not particularly accomplished in the Alchemical arts, and may have been even more of a charlatan than the average practitioner of that particular craft. At one point Thomas Eyre found him in the Church in the possession of suspicious books

and had him arrested. In my previous life I was a chemist—a real one, not one of our more mystical antecedents—and I can only wonder if grandfather Thomas would have cast a scornful eye towards some of my books, many of which would surely have seemed blasphemous at the time. Perhaps not, since the Saint Thomas Alchemist was released after only a short incarceration, with his books being returned to him.

Returning to the Eyre Monument, the most interesting feature for me is to be found at its base. As shown in the image below, the children of Thomas and Elizabeth are represented beneath their parents. Six boys (shown as adults, as evidenced by their ubiquitous facial hair) are on the left side, and five girls to the right. One son and one daughter are holding skulls and beneath them are three figures depicting children who died in infancy. The interesting fact is that the number of offspring shown totals fourteen, while the text above Elizabeth states the couple had fifteen children.

I believe that the missing child may be John Ayer, my ninth great-grandfather. It is known that John was a Puritan in America, and it is also the case that there are no known records relating to his immigration. It is believed that he and his family sailed to America on a ship named the James, because that ship also carried some of his neighbors, however, he does not appear on any of its passenger lists. Puritans were frequently persecuted in England in that era, which is why many left for America in the first place, and apparently they often kept their finances and travel plans secret to avoid arousing undue suspicion. It is possible, therefore, that his parents aided him in that regard by requesting his figure be omitted from their monument. Of course, it is also possible that whoever carved the Eyre monument was simply not very good at arithmetic.

In either case John and his family’s emigration in the 1630s brought to a close my Ayers lineage’s five-hundred-year presence in Wiltshire. I definitely enjoyed my brief visit to that area, which had been important to my family for such a long time. Wiltshire is beautiful, and full of interesting sights, and Salisbury is one of England’s most appealing small cities. Once again, history has shown that my family has lived in some amazing places, then, for whatever reason, left for somewhere else. I suppose I can’t be too critical of that, since over the years I have lived in five very different locations, with a more radical relocation potentially looming. Perhaps my family proves that home is wherever you happen to be at any given point in time.

Update—September 2020:

During the summer of 2020, restoration of the Eyre Memorial in St. Thomas Church progressed, despite the health crisis ongoing at the time, and has now been completed. A member of the Church was kind enough to send me an image of its now-proud appearance. Such a gratifying improvement!