Following the Beagle

In the wake of some true explorers

Though I never intended for it to do so, part of the way through the Tour of Gondwana I realized that my route brought me to many of the same places seen in bygone ages by some of the most impressive explorers from our collective past. Men whose desire for knowledge and love of travel took them on epic journeys to distant parts of the World, and into lands then largely unknown to their peers. Men with names like Ferdinand Magellan, Ibn Battuta, James Cook, Marco Polo, Wang Dayuan, Abel Tasman, and certainly numerous others whose wanderings were not preserved for posterity and have sadly been forgotten. In no way whatsoever do I mean to imply that my little Tour represents the same level of achievement that these talented navigators and journeymen previously accomplished. To be sure, Cook was never able to withdraw additional cash from an ATM in Australia, or Dayuan could not quickly check the Web for the most recent weather forecast. Not to mention the abilty to purchase a refreshing chilled beverage at a local kiosk, or the thousands of kilometers of surfaced roadways throughout the World that made the completion of my endeavor largely a foregone conclusion. That my Tour pales in comparison does not matter to me in the slightest and in no way lessens the fascination that I felt when I realized that Polo, over 700 years earlier, walked about among the pagodas of Bagan, just as I had, or that Magellan's ships sailed the same chilly straits that my bike and I also crossed, five centuries hence. The fact that all of the lands I saw are now "known" after centuries of visitations also mattered not, as they were all new to me, and seeing them for the first time usually brought forth the same feelings of amazement that I'm sure these earlier travelers felt upon their first sightings.

However, as interested as I was in all of the names mentioned above, and the places where our routes overlaid, there was one exploration, or, more precisely, one set of explorations, which captivated my attention more than any other. Those journeys were not made by an individual, but rather many intrepid explorers, who all shared one common mode of travel. Specifically, they were all crew on board one of the most important ships in history, an unremarkable little craft, for its time, that overachieved in its service, and in the end changed the way humanity comprehends the World and its place within it. That ship was none other than the HMS Beagle.

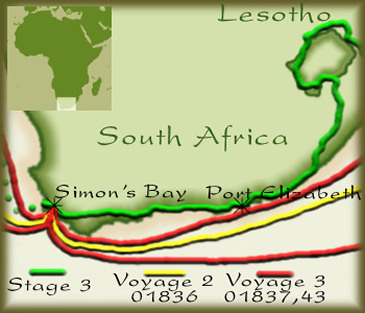

The Beagle was a ship without a purpose when it was built in 01820, and sat idle for the first five years of its life. That all changed when Britain's Royal Navy commissioned the ship to undertake what would become three extended surveying and mapping expeditions in the Southern Hemisphere. The first voyage lasted from 01826 to 01830 and involved a survey of the cone of South America. Following that was an even more impressive second voyage, from 01831 to 01836, which was to be a circumnavigation and included additional and extensive work in South America, as well as Australia and intermediate points. The ships third, and final, expedition was a return to Australia in the years 01837 to 01843. Of these, it is the second voyage which earned the ship its place in history. That was largely due to the presence on board of a Mr. Charles Robert Darwin, a young graduate with a fairly nebulous career path ahead of him. Darwin joined the crew of the Beagle ostensibly as a naturalist, a task to which he would excel beyond description. Today, it is generally assumed that his place aboard the ship was primarily created to provide intellectual companionship to its captain for the second voyage, Robert Fitz-Roy.

However, while Darwin's observations, and, more importantly, the conclusions he drew from them, largely created the fame that still surrounds the Beagle, all three voyages were outstanding examples of detailed observational practices and navigational skills, not to mention the always-necessary ability to adapt and survive in faraway lands. On this page, I provide a chronicle of the locations where my Tour route crossed, or approached, the courses of the three Beagle voyages, and compare my observations of those places with those made by members of its crew. The latter include Fitz-Roy (Voyages 1 & 2), Darwin (Voyage 2), and Midshipman, later Commander, John Lort Stokes (Voyages 1-3).

The chronology presented here follows that of my Tour, and we begin with my arrival in Australia for Stage 1:

Stage 1 Congruences

Southeastern Australia

Like the Beagle, I reached Australia by sea, making my first landfall after entering the Port Phillip Bay on board the MV Direct Kestrel. This must have been a considerably different experience for me, compared to the Beagle crew, considering that my ship was a container ship, as opposed to a wooden barque, and that my destination was a major modern city. However, my impressions of the Bay, even at the early hour of our arrival, were almost identical to those of Stokes, namely a placid body with a deceptively low shore.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The first appearance of Port Phillip is very striking, and the effect of the view is enhanced by the contrast with the turbulent waves without and in the entrance. As soon as these have been passed, a broad expanse of placid water displays itself on every side; and one might almost fancy oneself in a small sea. But the presence of a distant highland forming a bluff in the North-East soon dispels this idea. Besides this bluff (called by the natives Dandonong) Arthur's Seat, and Station Peak are the principal features that catch the eye of the stranger."

The Direct Kestrel crosses Port Phillip Bay on the way to Melbourne

As can be seen in the images above and below, the metropolitan area of Melbourne presents a distinctly more crowded and urban appearance than the same area did when the Stokes first observed the region in 01838.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Proceeding up the Yarra-yarra, we found that about two miles from the mouth, the river divides, one branch continuing in a northerly direction, and the other, a narrow sluggish stream, turning suddenly off to the eastward. The banks are so densely wooded, that it is seldom if ever that its surface is ruffled by a breeze.The township of Melbourne on its north bank, five miles from the river's mouth, we found a very bustling place. Nearly two thousand persons had already congregated there, and more were arriving every day, so that great speculation was going on in land. We were delighted with the park-like appearance of the country, and the rich quality of the soil. This was the most fertile district we had seen in all Australia; and I believe everyone allows that such is the case. Its reputation indeed was at one time so great, that it became the point of attraction for all settlers from the mother country, where at one time the rage for Port Phillip became such, that there existed scarcely a village in which some of the inhabitants, collecting their little all, did not set out for this land of promise, with the hope of rapidly making a fortune and returning to end their days in comfort at home. Everyone I think must leave with such hopes; for who can deliberately gather up his goods and go into a far country with the settled intention of never returning?"

However, even in the mid-nineteenth century, things have a way of changing more quickly than one would expect, though I'm sure it took many more decades still for Melbourne to come to resemble the city that I saw.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The last three years had also made great additions to the buildings of William Town; but Melbourne had so increased that we hardly knew it again. Wharfs and stores fronted the banks of the Yarra-yarra; whilst further down, tanners and soap-boilers had established themselves on either side, where, formerly, had been tea-tree thickets, from which the cheerful pipe of the bell-bird greeted the visitor. Very different, however, were now the sights, and sounds, and smells, that assailed our senses; the picturesque wilderness had given place to the unromantic realities of industry; and the reign of business had superseded that of poetry and romance."

The Yarra River in Melbourne

Observing wildlife was a passion of mine during the Tour, and apparently, in addition to Darwin, the rest of the Beagle crew felt the same way. I was pleased to see that Black Swans are still fairly common in that part of Australia, along with many other examples of that continent's exquisite avifauna.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Black swans were very numerous, and it being the moulting season, were easily run down by the boats. Their outstretched necks and the quick flap of their wings as they moved along, reminded us forcibly of a steamboat. At this season of the year when the swans cannot fly, a great act of cruelty is practised on them by those who reside on the Islands in Bass Strait, and of whom I have before spoken as sealers: they take them in large numbers and place them in confinement, without anything to eat, in fact almost starve them to death, in order that the down may not be injured by the fat which generally covers their bodies.

A pair of Black Swans on a pond in Victoria

At the time of the Beagle's third voyage, Tasmania, also known then as Van Diemen's Land, was the part of the continent that had received the greatest influx of Europeans, and which most closely resembled the lands from whence they came.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The first view of Launceston, the second town in Tasmania, is very pretty. The valley of the river expands as you approach, and over a low tract of land on the east bank, the straggling mass of buildings forming the town is descried. Though very healthy it lies on a kind of flat, backed with open woodland undulations at the junction of the North and South Esks; and, during the winter, is subject to fogs so dense that many persons well acquainted with the town frequently lose themselves. "

Prince's Square, in Launceston, Tasmania

That also meant that Tasmania was the epicenter for the extermination of the aborigines which had lived on the continent for tens of millennia. While the chroniclers of the Beagle voyages frequently revealed their steadfast beliefs in the virtues of the "civilization" of which they were a part, and the inevitability and justification of its spread around the globe, they were also not unwilling to confess to its faults, immoralities, and some of its excesses. The two passages below, dealing with the genocide of the Tasmanian people, provide a glimpse of the shifts in attitudes just beginning to emerge in the society of the time.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:"All the aborigines have been removed to an island in Bass's Straits, so that Van Diemen's Land enjoys the great advantage of being free from a native population. This most cruel step seems to have been quite unavoidable, as the only means of stopping a fearful succession of robberies, burnings, and murders, committed by the blacks; but which sooner or later must have ended in their utter destruction. I fear there is no doubt that this train of evil and its consequences, originated in the infamous conduct of some of our countrymen. Thirty years is a short period, in which to have banished the last aboriginal from his native island,—and that island nearly as large as Ireland. I do not know a more striking instance of the comparative rate of increase of a civilized over a savage people.Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:The correspondence to show the necessity of this step, which took place between the government at home and that of Van Diemen's Land, is very interesting: it is published in an appendix to Bischoff's History of Van Diemen's Land. Although numbers of natives were shot and taken prisoners in the skirmishing which was going on at intervals for several years; nothing seems fully to have impressed them with the idea of our overwhelming power, until the whole island, in 1830, was put under martial law, and by proclamation the whole population desired to assist in one great attempt to secure the entire race."

"There appear to me to be the means of tracing this national crime to the individuals who perpetrate it; and it is with the deepest sorrow that I am obliged to confess that my countrymen have not, in Tasmania, exhibited that magnanimity which has often been the prominent feature in their character. They have sternly and systematically trampled on the fallen. I have before remarked that they started with an erroneous theory, which they found to tally with their interests, and to relieve them from the burden of benevolence and charity. That the aborigines were not men, but brutes, was their avowed opinion; and what cruelties flowed from such a doctrine! It is not my purpose to enter into details; I will only add that the treatment of the poor captive native by her inhuman keeper was in accordance with the sentiments prevailing, at one time, in the colony, and would not have received the condemnation of public opinion."

While the Beagle spent a considerable amount of time painstakingly crossing and recrossing the Bass Strait as part of its surveying mission, my two crossings of that body of water were considerably more rapid and comfortable, if not interesting, as I employed the fast overnight ferry, the Spirit of Tasmania, shown below, docked at Devonport.

Devonport, Tasmania, and the Spirit of Tasmania ferry

Darwin made several land excursions on his own during the second voyage, which allowed his path and mine to cross more easily, at least as far as I was concerned. The first occasion we covered the same earth was in New South Wales, when he made a trek from Sydney to Bathurst. His observations and mine were remarkably similar, that that region was no longer what it had once been, an area filled with wildlife and untouched nature.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:

"I hired a man and two horses to take me to Bathurst; a village about one hundred and twenty miles in the interior, and the centre of a great pastoral district. By this means I hoped to get a general idea of the appearance of the country. On the morning of the 16th (January) I set out on my excursion. The first stage took us to Paramatta, a small country-town, the second to Sydney in importance. The roads were excellent, and made upon the MacAdam principle: whinstone having been brought for the purpose from the distance of several miles. The road appeared much frequented by all sorts of carriages; and I met two stage-coaches. In all these respects there was a close resemblance to England; perhaps the number of alehouses was here in excess. The iron gangs, or parties of convicts, who have here committed some trifling offence, appeared the least like England; they were working in chains, under the charge of sentries with loaded arms. The power, which the government possesses, by means of forced labour, of at once opening good roads throughout the country, has been, I believe, one main cause of the early prosperity of this colony."

"The number of aborigines is rapidly decreasing. In my whole ride, with the exception of some boys brought up in the houses, I saw only one other party; these were rather more numerous than the first, and not so well clothed. This decrease, no doubt, must be partly owing to the introduction of spirits, to European diseases (even the milder ones of which, as the measles, prove very destructive), and to the gradual extinction of the wild animals. It is said that numbers of their children invariably perish in very early infancy from the effects of their wandering life. As the difficulty of procuring food increases, so must their wandering habits; and hence the population, without any apparent deaths from famine, is repressed in a manner extremely sudden compared to what happens in civilized countries, where the father may add to his labour, without destroying his offspring."

The Blue Mountians near Lithgow, NSW

We both spent a brief period wandering through he forests of the Blue Mountains, and I suspect that each of us would have liked to done so for a little longer. While I agree somewhat with Darwin's lament about missing deciduous forests, I certainly also appreciated the style of vegetation to be found there and the unique hues it gives the countryside year round.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:"The trees nearly all belong to one family; and mostly have the surface of their leaves placed in a vertical, instead of as in Europe, a nearly horizontal position: the foliage is scanty, and of a peculiar, pale green tint, without any gloss. Hence the woods appear light and shadowless: this, although a loss of comfort to the traveller under the scorching rays of summer, is of importance to the farmer, as it allows grass to grow where it otherwise could not. The leaves are not shed periodically : this character appears common to the entire southern hemisphere, namely, South America, Australia, and the Cape of Good Hope. The inhabitants of this hemisphere and of the intertropical regions, thus lose perhaps one of the most glorious, though to our eyes common, spectacles in the world,—the first bursting into full foliage of the leafless tree. They may, however, say that we pay dearly for our spectacle, by having the land covered with mere naked skeletons for so many months. This is too true; but our senses thus acquire a keen relish for the exquisite green of the spring, which the eyes of those living within the tropics, sated during the long year with the gorgeous productions of those glowing climates, can never experience."

One place that I am sure he and I touched the exact same piece of ground was at Victoria Pass, near Lithgow, though it was otherwise an unremarkable pass as far as I was concerned. The road, however, presumably had been upgraded more than once in the intervening 180 years.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:"Soon after leaving the Blackheath, we descended from the sandstone platform by the pass of Mount Victoria. To effect this pass, an enormous quantity of stone has been cut through; the design, and its manner of execution, would have been worthy of any line of road in England,–even that of Holyhead. "

Victoria Pass near Lithgow, NSW

Mr. C. R. Darwin:

"Early on the next morning, Mr. Archer, the joint superintendent, had the kindness to take me out Kangaroo-hunting. We continued riding the greater part of the day, but had very bad sport, not seeing a kangaroo, or even a wild dog. The greyhounds pursued a kangaroo rat into a hollow tree, out of which we dragged it: it is an animal as big as a rabbit, but with the figure of a kangaroo. A few years since, this country abounded with wild animals; but now the emu is banished to a long distance, and the kangaroo is become scarce; to both, the English greyhound is utterly destructive. It may be long before these animals are altogether exterminated, but their doom is fixed. "

At Lithgow, our paths diverged for a considerable while. If that town was present when Darwin visited, he neglected to mention it, and if it did I'm sure it looked much different than it did when I saw it.

The Lithgow Central Business District

Northeastern Australia

The Beagle's third voyage passed along the coast of Queensland on two occasions, but as that section of coast had previously been charted, the ship made few stops there. I, by nature of my land-based route, of course saw much more. For example, the ship's crew missed out on a relaxing visit to the beautiful, but sandy, Fraser Island, a location which could also have provided them with plenty of fresh water.

A beach on Fraser Island, near Sandy Cape

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:

"Behind these isles we saw numerous blue streaks of smoke from the fires of the natives, indicating the state of population on the slope of that lofty range of hills, which may be called the Cordillera of Eastern Australia, and which at this point, tower to a great height, overlooking the coast. We were abreast about noon of its most remarkable feature, Mount Hinchinbrook, in latitude 18 degrees 22 minutes South, rising to the height, according to our observations, of 3500 feet. "

On the other hand, I did not always get to see everything that I wished either. While Hinchinbrook Island made an impression on Stokes from a distance, I was forced to settle for a long-rage view as well, since I did not have the license required to rent a canoe to cross the narrow sound to the island. Sometimes, I envied the ability of past travelers to go wherever they pleased.

Hinchinbrook Island, coastal Queensland

One notable occasion where I really had the upper hand on the Beagle crew was at the Great Barrier Reef. While they encountered it for most of its distance, my experience was unquestionably more rewarding, as I was able to suit up on one occasion and see it at close range. Sometimes certain technologies are worth their price.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The opening through which Captain Cook passed out to sea, bore about North by East 9 miles, the outer line of the Barrier Reef, curving from thence to the North-West, and following the trend of the land. When this singular wall of coral, the most extensive perhaps in the world, is surveyed, it will I think be found to follow the direction of the coast it fronts with such exactness, as to leave little doubt that the vast base on which rests the work of the reef-building Polypifers, was, contrary to the opinion which I am aware prevails, upheaved at the same time with the neighbouring coast of the Australian continent, which it follows for a space of upwards of a hundred miles.From the elevation on which I stood, I had an excellent view of some reefs within the Barrier; whether they encircled an islet, or were wholly beneath the water, their form was circular, although from the ship, and indeed anywhere, viewed from a less height, they appeared oval-shaped. This detection of my own previously erroneous impressions, seemed to account for the recurrence in charts of elongated-shaped reefs, others having doubtless fallen into the same error. It is very remarkable that on the South-East or windward side of these coral reefs, the circle is of a compact and perfect form, as if to resist the action of the waves, while on the opposite side they were jagged and broken."

The Great Barrier Reef, off the coast near Cairns

Northern Australia/TimorLeste

In the vast lands of northern and western Australia, where towns are infrequent and widely spaced, port towns even more so, places where my route crossed the Beagle's were a little more uncommon. The first of these was a simple river crossing for me, using a nice, though uninteresting, modern bridge, but a much more important event for the crew of the ship, as they discovered the first of a few new rivers they would survey on the third voyage, namely the Adelaide River, so named for the Queen Dowager of the time.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"On returning to the ship we found that Mr. Fitzmaurice had arrived, bringing the expected, and very gratifying intelligence, that a large river with two branches, running South-East and South, with a depth of four fathoms, emptied itself into the head of the bay. The joy a discovery of this nature imparts to the explorer, when examining a country so proverbially destitute of rivers as Australia, is much more easily imagined than described. It formed a species of oasis amid the ordinary routine of surveying, rousing our energies, and giving universal delight. The castle-builders were immediately at work, with expectations beyond the pale of reason. ""Taking the return tide, we passed the night in the fourth reach; very stringent orders were given to the watch to keep a sharp lookout for alligators, as a great many had been seen during the day, while we knew that on the previous night a monster of this description had attempted to get into one of the boats. We had fired at several, but with one exception had done no mischief. To be roused by the noise of the boat's keel or side grating harshly against the scaly back of an alligator, is far from being a pleasant occurrence, and on such occasions I generally found myself clutching a pistol, always kept near me, for the purpose of executing judgment upon the very first flat head that showed his nose above the gunwale. "

A croc floating in the Adelaide River

The next stop is a little confusing, but rather important for our story. During the third voyage, the Beagle crew named a sizable harbor on the northern coast, Port Darwin after their comrade from the earlier voyage. Thirty years later a settlement was built there, which was given the name Palmerston. Upon creation of the Northern Territory in 01911, however, its name was changed to Darwin as well, and the city, now the territorial capital, grew to become the largest on the entire northern coast. The city and the body of water were to be the first of several geographic features named after the ship, or members of its crew, that I would encounter during the Tour.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The other rocks near it were of a fine-grained sandstone: a new feature in the geology of this part of the continent, which afforded us an appropriate opportunity of convincing an old shipmate and friend, that he still lived in our memory; and we accordingly named this sheet of water Port Darwin. A few small bamboos grew on this head; the other trees were chiefly white gums."

Sunrise at the harbor in Darwin, Northern Territory

Both the Beagle and I made excursions away from the continent to the islands lying north of its coast. However, the ship ventured there a handful of times, while I did so, rather regrettably, only once. Though we did not go to exactly the same places, the observations we made still revealed the similarities of different parts of the Indonesian archipelago even after all the ensuing years. For example, the stilt houses that Stokes described on Timor Laut, a different island now known as the Tanimbar Islands, were strikingly similar to the traditional ceremonial buildings I saw on Timor itself.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The houses, all raised on piles six or eight feet above the ground, could only be entered by means of a ladder leading through a trapdoor in the floor. The roofs neatly thatched with palm leaves, and formed with a very steep pitch projected considerably beyond the low side-walls, and surmounted at the gables by large wooden horns,* richly carved, from which long strings of shells hung down to the ground, giving the village a most picturesque appearance. The houses were arranged with considerable regularity, so as to form one wide street of considerable extent, from which narrow alleys branched on each side."

Ceremonial Buildings in Timor Leste

My very enjoyable visit to Timor took place wholly on the part of the island that is the young nation of Timor Leste. The Beagle called the western town of Kupang on a few occasions, including one excursion in small craft to acquire Timorean ponies in order to venture into the continental interior. The two ends of Timor have had exceedingly different histories, leading to distinct cultures today, not to mention political and miltary conflict, but in geographical terms, I felt that I saw enough of the island to get a feel for what the crew had observed earlier.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Many of the Timorees have really handsome features, strikingly different from the Malays. Their hair, which is neither woolly nor straight, but crisp, and full of small waves, is worn long behind, and kept together by a curiously formed comb. There is altogether a degree of wildness in their appearance that ill accords with their situation; for nearly all the Timorees in Coepang are slaves sold by the Rajahs of the different districts, the value of a young man being fifty pounds."

A man rides a Timor pony, Viqueque, Timor Leste

While the Beagle encountered many mighty rivers during its first two voyages, in Australia, the driest of continents, such occurrences were rarer. So the discovery of the Victoria, the largest river in the northwestern part of the continent, caused quite a stir among the crew, and led to a long inland mission to describe its banks. For me the river was merely a nice counterpoint to the featureless plains of the region.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"As we advanced, the separations in the range became more marked and distinct, as long as the light served us, but presently darkness wrapped all in impenetrable mystery. Still we ran on keeping close to the eastern low land, and just as we found that the course we held no longer appeared to follow the direction of the channel, out burst the moon above the hills in all its glory, shedding a silvery stream of light upon the water, and revealing to our anxious eyes the long looked-for river, rippling and swelling, as it forced its way between high rocky ranges. Under any circumstances the discovery would have been delightful, but the time, the previous darkness, the moon rising and spreading the whole before us like a panorama, made the scene so unusually exciting, that I forbear any attempt to describe the mingled emotions of that moment of triumph. As we ran in between the frowning heights, the lead gave a depth of eighteen and twenty fathoms, the velocity of the stream at the same time clearly showing how large a body of water was pouring through. "This is indeed a noble river!" burst from several lips at the same moment; "and worthy," continued I, "of being honoured with the name of her most gracious majesty the Queen:" which Captain Wickham fully concurred in, by at once bestowing upon it the name of Victoria River."

The Victoria River

Of course, I cannot say with any certainty, but the section of the River in the image below certainly seems like the place that Stokes describes so eloquently.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Taking advantage of the cool of the morning, we moved off with the early dawn. A fine sheet of water lay before us, and everything promised well. The vegetation looked stronger and richer. Above the growth of acacias and drooping gums, that leant over the banks kissing their reflection in the limpid waters, rose on each side high broken ranges. Their heights had round summits, just beneath which, in some, could be traced a low line of cliffs, so singularly characteristic of Sea Range. The very marked dip in the strata did not extend beyond the latter, and here I could not detect any. Flights of large vampires, whistling ducks, many-coloured parakeets, and varieties of small birds, made the river quite alive, and their continued cry of alarm gave vivacity to the scene, and disturbed the stillness that had reigned there for years."

The Victoria River, farther upstream

Like certain members of the crew, I also paid attention to the plant life I saw along my route. One of the more important species I saw in Australia was the Boab, which Stokes describes, rather allegorically, as the "Gouty-Stem Tree". His alternate identification as a member of Adansonia turned out to be correct, as the Boab is the Australian example of that primarily Madagascan group. Other examples beyond the rather petite tree shown below, seen along the Victoria River, were much more massive and significantly thicker, or should I say, "Goutier".

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Among the most curious vegetable productions along its banks are the silk cotton-tree and the gouty-stem tree. The latter has been already mentioned by Captains King and Grey, and here attains a great size: it bears a very fragrant white flower, not unlike the jasmine; the fruit is used by the natives, and found to be a very nutritious article of food, something similar to a coconut. Not having previously noticed it in this neighbourhood I conclude this to be the northern limit of its growth. "Here also I remarked the gouty-stem tree, figured by Captain Grey, and described by Captain King, as of the Nat. Ord. Capparides, and thought to be a Capparis; it also bears a resemblance to the Adansonia described in Captain Tuckey's Congo. This was but a small specimen in fruit, of which the following brief description may convey a tolerably clear idea. In shape it something resembled the coconut, with a gourd-like outside, of a brown and yellow colour. Its length was five inches, and diameter three. The shell was exceedingly thin, and when opened it was found to be full of seeds, imbedded in a whitish pulp, and of a not ungrateful taste."

A fairly small Boab tree growing alongside the Victoria River

Western Australia

A third river that I crossed, and which was also discovered by the crew, was the Fitzroy, in Western Australia. While that channel was honored by being given the name of the ship's former commander, it cannot be said, in all honesty, to be the most impressive of rivers, at least during the dry season, when I visited. I'm sure the gesture of the crew was appreciated by the man himself, nonetheless.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"All doubt about our being in the mouth of a river was put an end to by finding that, during the last of the ebb, the water was nearly fresh. This discovery was hailed by us all with a pleasure which persons only familiar with the well-watered and verdant fields of England cannot fully comprehend.Our success afforded me a welcome opportunity of testifying to Captain Fitzroy my grateful recollection of his personal kindness; and I determined, with Captain Wickham's permission, to call this new river after his name, thus perpetuating, by the most durable of monuments, the services and the career of one, in whom, with rare and enviable prodigality, are mingled the daring of the seaman, the accomplishments of the student, and the graces of the Christian--of whose calm fortitude in the hour of impending danger, or whose habitual carefulness for the interests of all under his command, if I forbear to speak, I am silent because, while I recognise their existence, and perceive how much they exalt the character they adorn, I feel, too, that they have elevated it above, either the need, or the reach of any eulogy within my power to offer!"

"At the end of this reach, which extended for a mile and a half in a South-East by South direction, the river was scarcely 50 yards wide, and the depth had decreased from 12 to 6 feet; the current, scarcely perceptible in the deep water, now ran with a velocity of from one to two miles per hour. Here, therefore, the Fitzroy may be said to assume all the more distinctive features of an Australian river: deep reaches, connected by shallows, and probably forming, during the droughts which characterize Australia, an unlinked chain of ponds or lagoons; and in places, leaving no other indication of its former existence than the water-worn banks and deep holes, thirsty and desolate as a desert plain."

The Fitzroy River, near Wilare Roadhouse, Western Australia

In this region, Stokes also vividly describes the most bothersome issue facing all travelers in the Outback of Australia. I have often heard others state that this problem has only been significant since large numbers of cattle were introduced onto the continent. However, Stokes' account, written when settlements on the Australian mainland were barely forty years old, and even younger in the west, seems to contradict that claim. It does seem oddly reassuring that, even then, visitors had to deal with the same annoyances as I did during the Tour.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Their habit of keeping the eyes almost closed, and the head thrown back, in order to avoid the plague of flies, under which this country seems to suffer, adds to the unpleasant expression of their countenance, and quite justifies the correctness of Dampier's account: "Their eyelids are always half-closed, to keep the flies out of their eyes, they being so troublesome here, that no fanning will keep them from coming to one's face; and without the assistance of both hands to keep them off, they will creep into one's nostrils, and mouth too, if the lips are not shut very close; so that from their infancy, being thus annoyed with these insects, they do never open their eyes as do other people, and therefore they cannot see far unless they hold up their heads, as if they were looking at somewhat over them." We found constant occasion, when on shore, to complain of this fly nuisance; and when combined with their allies, the mosquitoes, no human endurance could, with any patience, submit to the trial. The flies are at you all day, crawling into your eyes, up your nostrils, and down your throat, with the most irresistible perseverance; and no sooner do they, from sheer exhaustion, or the loss of daylight, give up the attack, than they are relieved by the musquitos, who completely exhaust the patience which their predecessors have so severely tried. It may seem absurd to my readers to dwell upon such a subject; but those, who, like myself, have been half-blinded, and to boot, almost stung to death, will not wonder, that even at this distance of time and place, I recur with disgust to the recollection."

Roebuck Bay, at Broome, Western Australia

Just to the north of Roebuck Bay, and the modern-day town of Broome, the ship gave its name to another geographical feature, a body of water now called Beagle Bay. Though I did not see the Bay itself, I did make a short side trip to the little village nearby, which bears the same name.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The land over it rises to an elevation of nearly 200 feet, and then again becomes low and sandy, opening out a bay, which from appearance promised, and wherein we afterwards found, good anchorage: it was named Beagle Bay, and may serve hereafter to remind the seamen who benefit by the survey in which that vessel bore so conspicuous a part, of the amount of his obligations to the Government that sent her forth, the skill and energy that directed her course, and the patient discipline by which, during her long period of active service, so much was done for the extension of our maritime knowledge. In the bight formed between this bay and Cape Baskerville we passed two high-water inlets; the mouths of both were fronted with rocky ledges. We anchored here, soon after midday, and had every reason to be satisfied with our berth. Beagle Bay is about three miles broad and seven deep; the country around is low and open, and traces of water deposit were visible in several spots to indicate its dangerous proximity to the sea."

Today, Beagle Bay is at the center of a fairly large Aboriginal territory, and is a very small center, comprising just a handful of small buildings. On the day I visited the community was seemingly deserted, but that was because most everyone was sleeping late after what must have been a rousing Corroboree the night before. I am still annoyed that I missed that interesting event by one day.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"The forenoon was devoted to the examination of this excellent anchorage, and a party was also despatched to haul the seine. On landing they were met by a party of natives, who saluted them in a manner which strikingly resembled the eastern mode. They had no weapon, save one kiley or boomerang, and bowed down until they almost kissed the water."

Mother-of-Pearl altar in the chapel at Beagle Bay

While the Beagle sailed along the west coast of the continent several times, they rarely stopped there, and Stokes seemed to be less than impressed by its features. At times, I felt the same way, with a few three-hundred kilometer sections of lonely highway to traverse, but at least I had the opportunity to stroll along a pleasant beach from time to time, such as the aptly-named "80-Mile Beach."

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"From that headland commenced a low, wearisome, sandy shore, which we traced for sixty-five miles in a South-West by West direction, looking in vain for some change in its character. Nothing beyond the coast sand-dunes, sprinkled with vegetation, and only twenty feet high, could be seen from the masthead, although the ship was within three miles of the beach. This cheerless aspect was heightened by the total absence of native fires, a fact we had never before observed in such an extent of country, and truly significant of its want of fertility. Still, in our sight it possessed a greater charm than it may, probably, in that of others; as every fresh mile of coast that disclosed itself, rewarding our enterprise whilst it disappointed our expectations, was so much added to the domains of geography. That such an extent of the Australian continent should have been left to be added to the portion of the globe discovered by the Beagle was remarkable; and although day by day our hopes of accomplishing any important discovery declined, a certain degree of excitement was kept alive throughout."

80-Mile beach, Western Australia

Stage 3 Congruences

Madagascar

The Beagle was not tasked with surveying the coast of Africa, so they did not see most of what I did during Stage 3. While on the way from Australia back to the Atlantic during voyages 2 and 4, the ship did pass fairly close to the southern tip of Madagascar. It is rather unfortunate that Darwin did not get a chance to explore that grand island, as there is a treasure trove of endemic species, both plants and animals, to be found there. In the early part of the 19th century, there were no port facilities on that part of the island, so there was little incentive for the ship to stop there. However, the spiny forest would have been an excellent place for a naturalist of the time to visit, and Darwin probably would have been able to find giant eggs shell fragments from the extinct elephant bird which were commonly found scattered about the ground in those days, but rare when I have visited. Surely he would have seen things there that would have aided him in the development of his grand ideas.

Cmnd. J. L. Stokes:"Southerly and westerly winds brought us in sight of Madagascar on the 16th, and on the same evening, aided by a southerly current of 2 knots an hour, we were just able to weather its South-East extreme. The features of this great island that were presented to our view approached the Alpine, and from a passing glimpse of the small hills near the shore, it appeared to be a fertile country. This portion of the globe is one of great interest to the world at large, especially when we know that, if considered as a naval or military station, it is scarcely equalled by any in the Indian Ocean; besides having a soil of the best description, and abounding also in mineral wealth, with timber fit for any purposes, and thousands of cattle running wild in its valleys."

The Southeastern coast of Madagascar, at Toalagnaro

Calls were made at the Cape of Good Hope during voyages 2 and 3, but they were primarily made for the purposes of refreshing the ship's stores. Darwin undertook a couple of brief excursions, but was largely frustrated in his attempt to see much in the way of flora and fauna. He might have enjoyed seeing the penguin colony at Boulders Beach, in Simon's Town, but there is no record of penguins living there in that time. The colony that exists there today was established by colonial penguins in 01982.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:"We sailed from Port Louis, on our way to the Cape of Good Hope, and on the evening of the 31st anchored in Simon's Bay. The little town offers but a cheerless aspect to a stranger's eye. About a couple of hundred, square, whitewashed houses, with scarcely a single tree in the neighbourhood, and very few gardens, are scattered along the beach, at the foot of a lofty, steep, bare wall, of horizontally-stratified sandstone.The next day I set out for Cape Town, which is twenty miles distant. Both towns are situated within the head-lands, but at the opposite extremities of a range of mountains, which extending parallel to the mainland, is joined to it by a low sandy flat. The road skirted the base of these mountains: for the first fourteen miles the country is very desert, and with the exception of the pleasure which the sight of an entirely new vegetation never fails to communicate, there was very little of interest. The view however of the mountains on the opposite side of the flat, brightened by the declining sun, was fine. Within seven miles of Cape Town, in the neighbourhood of Wynberg, a great improvement was visible, and here the country-houses of the more wealthy residents of the capital are situated."

Simon's Bay, near the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa

African Penguins at Boulders Beach

The view of the famous Table Mountain I obtained while departing the continent aboard the MSC Geneva was, when seen from a distance, at least, likely identical to what the crew of the Beagle witnessed. In both cases, it provided a dramatic send-off to we who were departing the continent.

Mr. C. R. Darwin:"In Cape Town it is said that the present number of inhabitants is about 15,000, and in the whole colony, including coloured people, 200,000. Many different nations are here mingled together; the Europeans consist of Dutch, French, and English, and scattered people from other parts. The Malays, descendants of slaves brought from the East Indian archipelago, form a large body. They are a fine set of men, and can always be distinguished by a conical hat, like the roof of a circular thatched cottage, or by a red handkerchief on their heads. The number of negroes is not very great; and the Hottentots, the ill-treated aborigines of the country, are, I should think, in a still smaller proportion. The first object in Cape Town which strikes the eye of a stranger, is the number of bullock-waggons. Several times I saw eighteen, and I heard of twenty-four oxen being all yoked together in one team. Besides these, waggons with four, six, and eight horses in hand, go trotting about the streets. I have as yet not mentioned the well-known Table Mountain. This great mass of horizontally stratified sandstone rises quite close behind the town to a height of 3500 feet: the upper part forms an absolute wall, often reaching into the region of the clouds. I should think so high a mountain, not forming part of an extensive platform, and yet being composed of horizontal strata, must be a rare phenomenon. It certainly gives the landscape a very peculiar, and from some points of view, a grand character."

Table Mountain, seen while at sea, near Cape Town

Islas Canarias

The Islas Canarias, today Spanish territory, have long been a crossroads for mariners in the Atlantic, and all three Beagle voyages called there, as did I during the transfer from Stage 3 to Stage 4.

Capt. R. Fitz-Roy:

"Early on the 6th we saw part of the island, and soon afterwards the upper clouds dispersed, and we enjoyed a magnificent view of the monarch of the Atlantic: the snow-covered peak glittering in the rays of the morning sun. Yet as our ideas are very dependent upon comparison, I suppose that persons who have seen the Himalaya Mountains, or the Andes, in all their grandeur, would not dwell much upon the view of Teneriffe, had it not become classical by its historical associations, and by the descriptions of Humboldt and many distinguished travellers."

As someone who has seen both the Himalaya and the Andes, I would not have minded seeing Tenerife as well. However, that was not to be for me, as the MSC Geneva called at the surprisingly urban city of Las Palmas, on Gran Canaria, an island whose peaks are somewhat smaller and less renowned. Later, I passed the archipelago a second time, on board the Repubblica Argentina, however, on that occasion we sailed right past the eastern islands of the group without stopping. Darwin was also disappointed in his goal of visiting Tenerife, which he had apparently wanted to do since he was a student. That was due to fears of an English cholera outbreak, which left the crew quarantined on board the ship during their call.

Arriving at Las Palmas harbor, on Gran Canaria

Continued in:

Part 2

Previous | Next

Main Index | Pre-Tour Index

Post-Tour Index | Articles Index

Slideshows

Main Index Pre-Tour Post-Tour Articles Previous Next |

About the Ship

Vital Statistics

Built: Woolwich Naval Dockyard, River Thames, England

Launched: May, 11 01820

Class and type: Cherokee-class brig-sloop (converted to a barque after voyage 1)

Tons burthen: 235 tons (242 tons for second voyage)

Length: 27.5 m

Beam: 7.5 m

Draught: 3.8 m

Masts: (length/diameter)

Lower-fore: 14.1 m/36 cm

Top-fore: 3.96 m/25 cm

Lower-main: 16.6 m/45 cm

Top-main: 3.96 m/25 cm

Topgallant-fore: 2.3 m/15 cm

Topgallant-main: 2.3 m/

15 cm

Bowsprit: 3.7 m/23 cm

Fore-lower Yard: 4.9 m/

28 cm

Fore-topsail Yard: 4.2 m/

20 cm

Fore-topgallant Yard: 3 m/

15 cm

Main-lower Yard: 5.2 m/

28 cm

Main-topsail Yard: 4.2 m/

20 cm

Main-topgallant Yard: 3 m/

15 cm

Main driver Boom: 5.7 m/

28 cm

Driver gaff Boom: 3.1 m/

19 cm

Jibboom: 2.7 m/20 cm

Spritsail-yard: 4.11 m/15 cm

Mizzenmast-lower: 4.6 m/

41 cm

Mizzen-topmast: 3 m/25 cm

Mizzen driver boom: 3 m/

19 cm

Crews

(upon departure)

Voyage 1:

Commander Pringle Stokes

Lt. E. Hawkes

Lt. W.G. Skyring

Master S.S. Flinn

E. Bowen, Surgeon

B. Bynoe, Asst. Surgeon

J. Atrill, Purser

J.L. Stokes, Midshp.

R.F. Lunie, Volnt.-1st.

W. Jones, Volnt.-2nd

J. Macdougall, Clerk

J. May, Carpenter

10 Royal Marines

40 men and boys

Voyage 2:

Commander Robert Fitz-Roy

Lt. J.C. Wickham

Lt. B.J. Sulivan

Master E.M. Chaffers

R. McCormick, Surgeon

B. Bynoe, Asst. Surgeon

G. Rowlett, Purser

J.L. Stokes, Mate

A. Derbishire, Mate

P.B. Stewart, Mate

A. Mellerersh, Midshp.

P.G. King, Midshp.

A. B. Usborne, Asst. Master

C. Musters, Volnt.-1st.

J. May, Carpenter

E.H. Hellyer, Clerk

8 Royal Marines

35 men and boys

3 captives from

Tierra del Fuego

R. Mathews, Missionary

A. Earl, Artist

G.J. Stebbing, Instrument Maker

S. Covington, Fiddler

C. R. Darwin, Naturalist

Voyage 3:

Commander John Clements Wickham

Lt. J.L. Stokes

Lt. J.B. Emery

Lt. H. Eden

Master A. B. Usborne

B. Bynoe, Surgeon

T. Tait, Asst. Surgeon

J.E. Dring, Clerk

B.F. Helpman, Mate

A.T. Freeze, Mate

L.R. Fitzmaurice, Mate

T.T. Birch, Mate

W. Tarrant, Asst. Master

J. Weeks, Carpenter

C. Keys, Clerk

T. Sorrell Boatswain

8 Royal Marines

40 men and boys

Lt. G. Gray, and party to explore the interior of Australia

(Data from Thompson and Wikipedia)

Sources of Information

Keith S. Thomson

HMS Beagle: The Story of Darwin's Ship

The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online

Collection Index

John Lort Stokes

Discoveries in Australia

Vol 1. & 2

AboutDarwin.com

The HMS Beagle Project