Leafy Gondwana

The green life of Gondwana;

ancient and beautiful

O bserving the structure, ecological functions, and, especially, the beauty of the plant life living in various environments is an activity that can help to pass the hours of a long tour. However, for someone like me, who is not well trained in botany, the practice can be a bewildering diversion indeed. The nature of seed dispersal allows plants to spread relatively quickly across large areas of the globe, making it hard to determine if a particular plant is a native species or an invader. Even more disruptive has been the meddling practices of humanity, whose members transplant species without care, for agricultural, economic, or fashion-enhancing reasons. It took quite a bit of effort for me to determine whether a specific tree species had previously wiped out all of the endemic forests of a certain locale, or if an especially beautiful wildflower was actually a contrived hybrid that had escaped from someone's garden. Given enough time, which I suppose I had during the Tour, and patient observations, I eventually began to see patterns in the natural and human-caused distribution of flora throughout modern Gondwana. Sometimes those could be tangible, like similar types of wood being raised for industrial purposes on different continents. In other cases more subtle relationships were apparent, such as the fact that in arid environments worldwide the majority of plants, though they may belong to very different taxonomic groups, display silvery-green leaves. Below are some of the botanic situations that I found particularly interesting, together with a collection of plants that I simply found to be very pretty. Though I did my best to identify what I saw, I cannot guarantee complete accuracy in that regard, however.

Aromatic and Agressive

One particular genus of tree that I was definitively able to establish as a human-spread product is Eucalyptus. Trees and shrubs in that group are true Gondwanan plants, being the dominant form of tree in Australia and naturally occurring in only a few other places. My prior experience with that type of tree had been limited to a familiarity with the aromatic oils that fill its leaves, and the annoying little seedpods that occasionally shoot off like a rocket after being run over by a narrow bike tire. However, while on the Tour it did not take me long to realize the extent which Eucalyptus trees have been established as a crop product around the world. Though I did not keep track intently, I believe that I saw Eucalyptus growing in all of the countries that I visited.

Early on I believed that may have been caused by a natural dispersal that occurred long ago, since many of the trees I saw appeared to be very old and some groves seemed like they might have been established for centuries. However, whenever I inquired about their presence, I always learned that they had been brought from Australia fairly recently and planted for commercial use. One reason for their export, their fast-growing nature, is probably what fooled me into thinking their presence may have been pre-colonial. In some locations it was easy to see the uses for which the trees had been planted. In Ethiopia, for example, the straight, branch-free trunks are used as pole stock for traditional homes, while in South Africa I rode though a number of huge plantations of Eucalyptus that serve the local pulp and paper industry.

The wide dispersal of these trees has not been without adverse effects, however. Their aggressive nature has often displaced whatever native species may have been present in an area, and this threatens biodiversity in important ecosystems, such as Madagascar. One specific effect I noticed was apparent in eastern Argentina, where a type of Eucalyptus was often the only type of large tree to be seen. In that case, I noticed that the Monk Parakeet seemed to prefer those trees as a source of food, or nesting locations, or both. That presumably has led to a large increase in their numbers in that region, possibly at the expense of other bird species. So by importing a new tree species, which spread quickly through the area, humans had once again brought about unintended consequences to a regional ecosystem.

Eucalyptus in Central Australia Row 1

In the Blue Mountains, N.S.W. | in Timor Leste Row 2

Growing around an Ethiopian house | in Argentina, with parakeet Row 3

Around Lake Titicaca in Bolivia Row 4

Actually African

Not to be confused with "American Aloe", which is a member of the Agave family,Agavaceae, the Aloes are attractive succulent plants native to Africa. A few species, notably aloe vera have been used as medicinal plants for many years. Southeastern Africa was the part of my route with the most examples, with Madagascar possessing some interesting types as well.

Aloes in South Africa | in Lesotho Row 1

In Madagascar | detail of leaf Row 2

In Swaziland | Swaziland Row 3

In South Africa Row 4

The Destroyer of Bicycle Tires

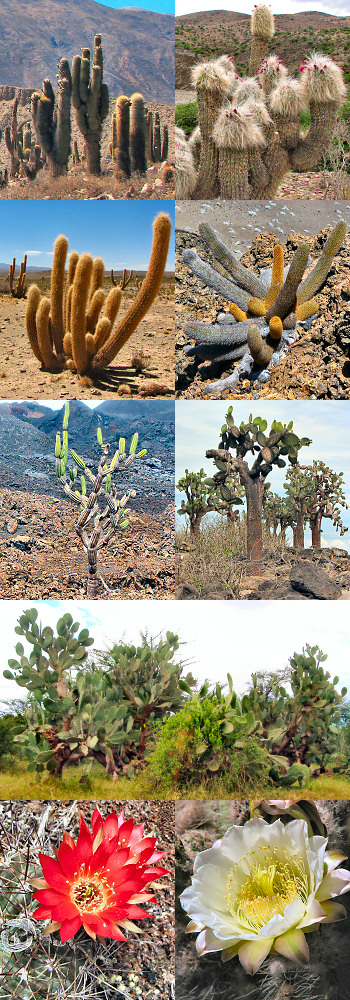

A different type of succulent, the members of the family, Cactaceae, the cacti, are famous both for their adaptations to very arid environments, as well as their piercing defensive spines. Originally exclusive to the Americas, various type of cactus species have been introduced to many parts of the world primarily for ornamental purposes, but also as a food crop for humans and animals. The main example of the latter is the sinister Prickly Pear, whose fruit is often one of the only dependable food sources in desert areas. I have also been told by people living in areas that are marginal for ranching that they are happy that prickly pear has been brought to their area, as their cows seem to like eating its thick, and horribly beweaponed, leaves. That last fact still amazes me, since cyclists should absolutely avoid Prickly Pear at all costs due to the plants propensity for inflicting numerous tire punctures upon even the slightest contact, an occurrence which has happened to me all too frequently. The central Andean region, and later Mexico, was the area on my route with the most interesting examples from this family.

Cacti: in Argentina | in Bolivia Row 1

In Bolivia | on Isla Bartolome, Galapagos Row 2

On Isla Isabela, Galapagos | on Isla Santa Fe, Galapagos Row 3

Introduced Prickly Pear in Madagascar Row 4

Red Cactus flower in Peru | white Cactus flower in Argentina Row 5

Cacti are only native to the Americas, though, thanks to convergent evolution, various succulents in other parts of the World can easily be confused for members of that family. An example is Euphorbia Candelabrum, a member of the family that includes poinsettias and spurges. Though they appear cactus-like, with thick, fleshy leaves, and spines, these plants, common in Ethiopia and the rest of east Africa, are not related to cacti at all.

Euphorbia Candelabrum in Ethiopia and Tanzania

Distinctly Confusing

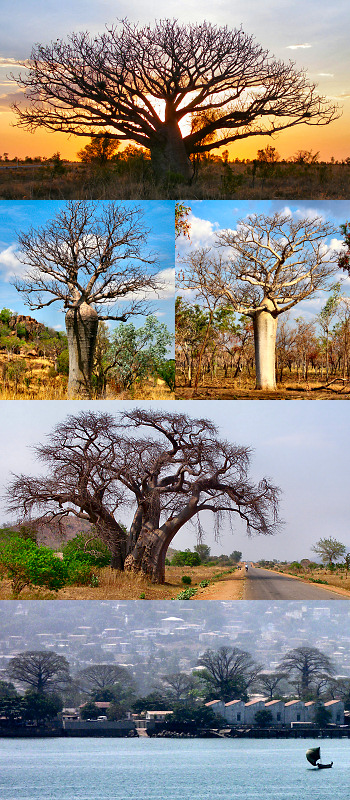

One of the true stars of the flora of Gondwana is the genus Adansonia, the mighty Baobabs. However, everything about these trees is confusing, from their odd appearances, earning them the nickname, "upside-down trees," to their evolutionary past. It had long been believed that the Baobabs had evolved on Gondwana before the break-up, and then evolved into separate species on the various lands of their modern range, Madagascar, Africa, and Australia. In fact, I also made this mistake and wrote about it on the front page of this very site. In reality, according to DNA analyses that were published while I was on the Tour, the genus first evolved more recently, on the order of 15-20 million years ago, well after the supercontinent had split apart. The tree's presence on different continents today must then have been the result of normal seed-dispersal pathways. Of course, in its early days, Africa Madagascar and Australia were considerably closer together than they are today, so dispersal across the oceans of that time would have occurred a little more readily.

My first encounters with baobabs during the Tour were in Western Australia, where the members of the local species are known as Boabs and possess a typically squat appearance. There are actually a few small groves growing in India and Sri Lanka, which I did not see during Stage 2, though I unknowingly passed tantalizingly close to the oldest examples in India, which grow in Karnataka. However, their origins are still unclear, but if they had been introduced to those lands by humans, their ages indicate that this occurred well before colonial times. In Africa, one species, the African Baobab is widespread throughout the more arid areas of the eastern and southern parts of the mainland. It has also spread along the west coast of the continent as far as Senegal, almost certainly with the aid of human trade. It is Madagascar, however, that is the epicenter of the Baobab realm, with six species being endemic to the island. The most impressive of these is the iconic Adansonia grandidieri, an endangered species found in the dry forests of the island's west coast. Cycling along the famous "Avenue of the Baobabs", near Morondava, which I did during my first tour in that country, is certainly a unforgettable experience.

A Boab in Western Australia Row 1

A Small Boab | another Boab Row 2

A Baobab in Malawi Row 3

Babobabs growing along the coast at Freetown, Sierra Leon Row 4

The Baobabs of Madagascar

The Afro-Alpine Zone

There are numerous places in the Gondwanan fragments where special environments have led to the evolution of very unique species. One spectacular example of this is the handful of mountaintops which comprise the Afro-Alpine Zone. My experience with that particular biome came after an exhilarating, though tiring, climb to the highest reaches of Mount Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania. The Great Rift Valley, west of the horn of Africa, where a new fragment of Gondwana is, even now, splitting off the main continent, is the home to a number of extinct and active volcanoes. Some of these are impressively tall, and that elevation causes their summits to escape the searing equatorial heat surrounding their bases, and subsist in a surprisingly frigid climate. In effect, this has caused the higher areas of these, and a few peaks in surrounding areas, to exhibit the same level of ecosystem isolation that would be found on certain oceanic islands. To survive in such an environment tropical plants needed to evolve various mechanisms to deal with the constant cold, especially at night. One example of this is Lobelia deckenii, a giant Lobelia, which is endemic to the Afro-Alpine zones. It protects itself against the nighttime cold by curling up its dense rosette of green leaves into a tight ball around the top of the plant. These unique plants are also distinctive due to their tall, but infrequent, inflorescences.

Lobelia Deckenii on Mount Kilimanjaro

An even more impressive example is the Giant Senecios, relatives of many smaller plants, such as the daisies, sunflowers, lettuces, and others, of the Asteraceae family. Like the lobelias, the species I saw on Kilimanjaro, Dendrosenecio Kilimanjari, has evolved a strategy to protect itself from freezing temperatures. In this case, it uses a protective sheath of older, dried leaves surrounding its trunk as a type of thermal insulation. However, while the lobelias can reach a fairly typical height, the Senecios grow to a truly impressive size, resembling small trees, or perhaps saguaro cacti, with their thick, branched trunks.

I had thought that when I descended off the mountain, I had seen my last example of such a plant. Indeed, I had for a long while. However, near the end of Stage 4, as I rode along a bumpy road though the Parque Nacional Purace, in the Andes of Colombia, I was taken aback by what appeared to be similar plants growing at an equally chilly elevation of 3,000 m.a.s.l. Examples, which take the local name Frailejones, are shown in the lower panels of the image below, and their resemblance to the giants on Kilimanjaro seemed undeniable. Only later did I learn that they were members of the genus Espeletia, which is also past of the Asteraceae family. I found it to be quite amazing that two such similar forms could arise independently in two different cold tropical environments, and seeing that relationship was certainly worth the effort required by that last climb over the Andes.

Dendrosenecio Kilimanjari, on Mount Kilimanjaro Row 1

Dendrosenecio Kilimanjari Row 2

Espeletia in Parque Nacional Purace, Colombia Row 3

Espeletia Row 4

Unique Endemics

While life that has spread across the dispersed parts of Gondwana is inherently interesting, there is something to be said for unique and endemic species that are confined to specific locations. I certainly appreciate the distinctiveness that such life forms add to our biosphere as a whole, and the best place along the Tour route, or anywhere in the World, for that matter, to see unique species is in Madagascar. The members of the family Didiereaceae are one of my favorite examples. Unique to the "Spiny Forests" of southern Madagascar, these tall, spindly, and spiny, succulent plants are a defining feature of that unique environment. Observing their odd appearance, as well as their attractive flowers, can help distract one from the exertions of cycling through what proved to be one of the roughest areas I encountered during the Tour. Another interesting aspect of this plant is that its minimal, and spine-surrounded leaves, provide an important food source for the area's resident lemur, the Verreaux's Sifaka. Exactly how this acrobatic primate can manage to feed on such a uncomfortable plant is beyond my understanding.

Didiereaceae of Madagascar

Another of Madagascar's unique plant types are the members of the genus Pachypodium, small succulents resembling miniature Baobabs, whose name corresponds to "thick-footed." Like their tree-sized cousins, these plants survive in arid conditions by growing a very thick base, with minimal amounts of leaves. I have seen a number of examples during my two tours of the island, but the most distinctive was probably the Elephant's Foot Plant, Pachypodium Rosulatum which is endemic to the area in and around Parc National Isalo.

Elephant's Foot Plant in Parc National Isalo Row 1

Elephant's Foot Flower | A tall variety of Pachypodium Row 2

Transplants & Migrants

I began paying attention to wildflowers more closely during my Canada Tour in 02004, though that can undoubtedly be a perplexing activity. Distinguishing between truly wild flowers and those found growing in the countryside that have been cultured by humans is a task at which I am not nearly proficient. Nevertheless, with time, it becomes a little easier to see both the similarities and differences of flowers found in widely-spaced lands. It was my observation that the most common colors of the wildflowers in the countries of the Tour are yellow and purple (and frequently yellow and purple), followed by white, orange, pink, red, blue, and green. I determined this, in part, thanks to numerous encounters with small plants decorated with slightly frumpy little purple and yellow flowers, of the type shown below. I first saw examples of these in Australia, and, somewhat surprisingly, continued to see variations on this design for the rest of the Tour. I now know that these are all members of the Solanaceae family, a very large grouping that includes a wide variety of species, including many commercialized or medicinal plants, such as, deadly nightshade, peppers, potatoes, tobacco, tomatoes, and petunias. Certainly, this family has spread worldwide by natural means.

Solanaceae growing in: Northern Territory, Aus. | Queensland, Aus.Row 1

Ethiopia | Colombia Row 2

Chile Row 3

I might have thought that the next example also made its way around the globe by its own efforts. However, I would have been wrong. My first encounter with Lantana, a shrubby flower-covered plant of the of the family Verbenaceae, came in New

South Wales, Australia, and at the time I thought, "Oh, what an attractive wildflower." As I continued to see the same pretty plants in many locations along the Tour route, I began to wonder if they were in fact not native wildflowers at all. Much later, once I had finally identified the plant, I learned that, indeed the Lantanas are native only to the neotropics, and were later spread to other parts of the World, most likely during the European colonial period. This example provides a case of translocating plants for aesthetic reasons leading to undesirable ecological consequences, as Lantanas have frequently become invasive and unwelcome weeds in many other lands. In fact, this situation has lead to one of the vernacular names for this plant, namely, The Curse of India.

Lantana growing in: NSW, Australia | Queensland, Australia Row 1

Papua New Guinea | Myanmar Row 2

Kenya | Argentina Row 3

Islas Galapagos | Ecuador Row 4

Ecuador Row 5

Another plant that first caught my attention in Australia, thanks to its unique and compellingly symmetric flowers, is shown below. The plants themselves are somewhat scruffy looking, with large pale-green leaves lining a woody stalk, and are often seen growing on roadsides, rocky hillsides, or other difficult environments. However, their thick, almost plastic-looking, white and purple flowers were among my favorites. I now know that this plant is Calotrope, a member of the Milkweed family, and is native to south Asia and the Middle East. However, I observed it growing in almost all the semi-arid environments I passed through during the Tour, and found it to be especially common near coastlines or lakeshores. This, I believe, is likely due to the large, air-filled seedpods the plant produces, which would seem to be ideally suited for spreading their seeds over large bodies of water.

Calotrope growing in: Queensland, Australia | N.T., Australia Row 1

India | Kenya Row 2

Malawi | Brazil Row 3

Colombia | Nicaragua Row 4

A second species in the genus Calotropis is Calotropis Gigantea which produces larger flowers, with varying amounts of purple and white. It is found primarily in South Asia and the archipelagoes of Indonesia and the Philippines, and so does not seem to be as efficient at colonizing other lands as its relative has been.

Calotropis Gigantea growing in: Timor Leste | Thailand Row 1

Thailand | Tanzania Row 2

Tropical Beauty

The tropics, in which a large faction of the Tour was located, are famous for the many beautiful flowers that grow there. Many of these have become standards in gardens worldwide, none more so that the Hibiscus, with over 200 species found throughout the tropical regions.

Hibiscus growing in: Islas Galapagos | Ethipoia Row 1

Bhutan | Brazil Row 2

Brazil | Argentina Row 3

Islas Galapagos Row 4

Frangipani, very beautiful flowering trees of the genus plumeria, are native to the neotropics,

but have been spread worldwide, notably to Hawaii, where they are almost iconic to that archipelago. Though I have seen them in many places, it took a long time for me to identify the species correctly, as I have often confused them with hibiscus.

Frangipani growing in: Sri Lanka | Queensland, Australia Row 1

Malawi | Swaziland Row 2

Burundi Row 3

With a decidedly unique flower structure, the Passion Flowers, of the genus, passiflora were one of the most compelling pant types I saw during the Tour. Though they are widely distributed around the World, most of my few encounters came during Stage 4, in South America.

Passion Flowers growing in: Colombia | Australia Row 1

Islas Galapagos | Peru Row 2

Orchids are probably one of the most diverse, widespread, and beloved, flower types on Earth. While the tropics hold the majority of the family's species, observing them in their natural habitat can be a rather uncommon experience, as they often grow high in trees and bloom infrequently. Many of the examples I saw were, therefore, being grown in specialty gardens. I unexpectedly found one of the best of such places in Tari, Papua New Guinea, where a man named Peter had painstakingly been converting his family's property into a huge outdoor Orchid conservatory. In the case of wild orchids, I was not always completely certain that I had properly identified the plants, though I am fairly sure about the examples pictured below.

Orchids growing in: Papua New Guinea | Central Australia Row 1

Papua New Guinea | Papua New Guinea Row 2

Ecuador | Colombia Row 3

Orchids growing in: Peru | Papua New Guinea Row 1

Papua New Guinea | Madagasacr Row 2

Papua New Guinea | Madagascar Row 3

Perhaps my choice for the most beautiful type of flower in the World is the water Lilies of the family, Nymphaeaceae. Not only are they especially attractive, but they hold special significance for some of modern Gondwana's societies. An example of that would be Sri Lanka, where I saw their blossoms by the thousands. Some of my favorite examples are shown below, though I believe the first is actually from a different family.

Water Lilies growing in: Paraguay | Colombia Row 1

Giant Liliypads, Pantanal, Brazil | Pantanal, Brazil Row 2

Thailand | Sri Lanka Row 3

Malawi | Queensland, Australia Row 4

The True Gondwanan Flora

Within the amazing range of plants I saw during the Tour, the types with the most relevance for me were examples of the grouping known as the Antarctic Flora. This could just as easily be named the South Gondwanan Flora, as its plants are living examples of the species that grew on the supercontinent when it was still joined. More precisely, the Antarctic Flora grew in the part of Gondwana which extended into the cool, damp, temperate latitudes of the southern hemisphere. Once the supercontinent broke apart, most of its fragments began to move northward towards the equator and the warmer climate found there, though Antarctica itself, of course, took the opposite path and became icebound at the southern pole. Therefore, today the only remnants of that ancient biome are found in the still-cool areas of eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, the Cape region of Africa, and southern South America. Human activity has reduced its range as well, and so seeing natural examples of this group of plants while on tour, is not exactly easy.

One member of the group that is still fairly common, and is one of my favorites, is the genus Dicksonia, the Tree Ferns. Their very presence lends an aura of prehistory to any forest, and makes one think that a dinosaur may come strolling along at any moment. Today they can be seen in most of the cool, damp regions of Gondwana, even in such unexpected places as the forests on the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania. However, to see the very best examples it is usually necessary to venture deep into the primary forest, and that exceptional environment is, sadly, harder to find than ever.

Tree ferns growing in: Tasmania, Australia Row 1

Victoria, Australia Row 2

Papua New Guinea Row 3

Tree ferns growing in: Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania Row 1

Madagascar Row 2

South Africa Row 3

Tree ferns growing in: Brazil Row 1

Ecuador Row 2

Isla Santa Cruz, Galapagos Row 3

Colombia Row 4

An example often smaller in size, though no less compelling, is the family Proteaceae, whose unusual flowers once decorated the forests of Gondwana. Though examples exist today on most of the Gondwanan fragments, Australia and the Cape region of Africa are the group's main ranges. The Banksias are a primary example in Australia, while in South Africa, the Proteas stand out. Both have multi-part flowers, often with numerous long stigmas, which make the members of the family easy to spot. In South Africa, the Proteas are part of the Cape Floral Kingdom, known locally as Fynbos, a biome so distinctive it has earned World Heritage Site Status for its remaining preserved areas. The King Protea, is also South Africa's national flower.

Banksias in Australia Rows 1,2

Proteas in South Africa Rows 3,4

Southern Beech was once a widespread component of the Gondwanan forests. Today, however, its range and abundance are more restricted. My sightings came in Tierra del Fuego, and southern Chile, though I had also seen Beech during my previous tour of New Zealand. The Burgundy color of their changing autumn leaves provided a nice diversion as I made the difficult ride through those regions.

Southern Beech growing on Tierra del Fuego

The family Araucariaceae could certainly make a claim to be the king of the Antarctic Flora. Many of its trees, especially the Auraucarias, exhibit a grand and distinctive appearance. Sprawling branches coated with spiky, triangular, leaves are characteristic of that genus, which give its trees a rather alien form. Unfortunately, significant groves of Araucaria today only grow naturally in small, widely scattered locations, all of which are difficult to reach. However, their unique nature has caused them to be planted in many diverse locations, especially in municipal parks. That, combined with their unmistakable shapes, makes them easy to spot.

With a little extra effort, I managed to get a reasonably good feel for the Antarctic Flora during the Tour. The impression that I received was that if I could somehow be transported back to the days of the original supercontinent Gondwana, with forests comprised of all of these special plants stretching off as far as one could see, I think that I would find it an especially beautiful place.

Bunya Pine in Qld., Australia | Bunya Pine planted in Valparaiso, Chile Row 1

Parana Pine in Brazil | Parana Pine in Brazil Row 2

Araucaria araucana in Coyhaique, Chile | Araucaria araucana cones Row 3

Araucaria araucana trunk | Araucaria araucana leaves Row 4

A Mixed Bouquet

Sometimes it is nice not to think about things too much and simply appreciate them for what they are. In that regard, here, finally, is a collection of some of the most beautiful flowers I saw during the Tour.

Flowers growing in: Brazil | Ecuador Row 1

South Africa | South Africa Row 2

Brazil | Australia Row 3

Australia | Argentina Row 4

Flowers growing in: Lesotho | Bhutan Row 1

Ecuador | Paraguay Row 2

Ethiopia | Botswana Row 3

Flowers growing in: Botswana | Argentina Row 1

South Africa | Australia Row 2

Ethiopia | Australia Row 3

Papua New Guinea Row 4

Flowers growing in: Ecuador | Lesotho Row 1

Mount Kilimanjaro | Madagascar Row 2

South Africa | Laos Row 3

Flowers growing in: Malawi | Argentina Row 1

South Africa | South Africa Row 2

Australia | South Africa Row 3

Flowers growing in: Kenya | Bhutan Row 1

South Africa | Brazil Row 2

Papua New Guinea | Papua New Guinea Row 3

Previous | Next

Main Index | Pre-Tour Index

Post-Tour Index | Articles Index

Slideshows

Main Index Pre-Tour Post-Tour Articles Previous Next |

Biomes of

the Tour

Though most regions contain numerous micro-climates, and the distinctions between various biomes are not always obvious, or even consistently labled within common descriptions, here are the major biomes I passed through during the Tour, as best as I could determine:

Tropical Rainforest

Isolated small pockets in protected areas within:

~Coastal Queensland

~Papua New Guinea

~Central Malaysia

~Eastern Madagascar

~Eastern Coastal Brazil

~Eastern Peru

Degraded Tropical Rainforest

~Coastal Queensland

~Papua New Guinea

~North-Coastal Australia

~Malaysia

~Southern Thailand

~Southern Myanmar

~Bangladesh

~Western Sri Lanka

~Western Coastal India

~Rwanda, Burundi

~Eastern Madagascar

~Eastern Coastal Brazil

~Eastern Peru

~Northern Colombia

~Panama

~Eastern Guatemala

~Belize

~Southern Coastal Mexico

Temperate Rainforest

~Western Tasmania

~Southwestern Chile

Degraded Temperate Rainforest

~Central Chile

Tropical Dry Forest

~Southern Ethiopia

~Zambia

~Western Costa Rica

Degraded Tropical Dry Forest

~Eastern Tasmania

~Southeastern Australia

~Eastern Interior Queensland

~Timor Leste

~Southern India

~Eastern Sri Lanka

~Western Tanzania

~Zambia

~Northern South Africa

~Swaziland

~Paraguay

~Northern Argentina

Tropical Montane Forest

~Papua New Guinea

~Bhutan

Degraded Tropical Montane Forest

~Papua New Guinea

~Northern Nepal

~Ethiopian Highlands

~Lesotho

~Peru

~Central Ecuador

~Southern Colombia

~South-Central Mexico

Monsoon Forest

~Laos

Degraded Monsoon Forest

~Cambodia

~Laos

~Northern Thailand

~Myanmar

~Northern India

Tree Savanna

~Northern Australia

~Northern Tanzania

~Central Brazil

Grass Savanna

~Northern Australia

~Southern Kenya

~Northern Tanzania

Temperate Steppe

~Interior New South Wales

~Southern Madagascar Highlands

~Eastern Interior South Africa

~Eastern Argentina

~Southeastern Patagonia

Dry Steppe

~Botswana

~Argentine Patagonia

Chaparral

~Cape Region South Africa

~Central Chile

Alpine Tundra

~Tibet

~Bolivia

~Peru

Xeric Shrublands

~Central/western Australia

~Botswana

~Southern Madagascar

Arid/Semiarid Desert

~Northern Kenya